The doorbell never stopped ringing at the home of Stefan and Olga Nemec as winter turned to spring in those giddy months of 1991 when Penguins fans could almost taste the champagne from their first Stanley Cup.

Among the reasons for their optimism was the fresh-faced, mullet-headed teenager residing in the split-level house at 3406 Dogwood Place in West Homestead. Third bedroom down the hall on the right. Isn’t that where Jaromir Jagr slept, according to the newspaper article?

The industrious Nemecs, who had fled the communist crackdown in Czechoslovakia in 1968, had lived quietly for more than a decade in the suburban Pittsburgh home they had built by hand. Jagr’s meteoric rise during the second half of his rookie season changed that.

Suddenly, every night was Halloween. Strangers walking up the driveway and standing on the front porch hoping to catch a glimpse of the strapping Penguins winger. Curiosity seekers in cars slowly creeping up and down a once sleepy street.

“There’s all these beautiful women, who are different from the women from back home, sending Jagr their panties in the mail,” said Phil Bourque, the Penguins’ radio analyst and two-time Cup champion. “It’s like a mini-Elvis came to town. People were swooning all over him.”

Jagr, who turned 50 on Monday in his hometown of Kladno, Czech Republic, where he still plays professionally, created an hysteria almost unrivaled in Pittsburgh sports history. His first season with the Penguins is a story thoroughly reported and well told through the eyes of many former teammates and those close to the organization.

But what of the family tasked with keeping him safe and out of trouble? What of the husband and the wife and their extended relatives charged with feeding him and paying his bills? They were the ones who served as gatekeepers and acted as the adults in the room when Jagr was out of the purview of Bob Johnson and Craig Patrick.They were the ones having to say “no” to the ebullient, sometimes moody kid who would evolve into the NHL’s second all-time leading scorer.

These were the responsibilities of Stefan and Olga Nemec, a pair of empty nesters already in their 50s. While the experience was mostly pleasurable and the lifelong bond with the Jagrs ultimately rewarding, there were intolerable moments, as well.

“Maybe my brother was too strict,” said Josef Nemec, 76. “But Stefan feel like he was 100 percent responsible for him. He don’t let (Jagr) go anywhere. They made a promise to the Jagr family that they would take care of him, and they did the best they could.”

In his autobiography, Jagr wrote in rich detail of his fulfilling, yet often frustrating time under Stefan Nemec’s roof.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Jagr writes. “My mother and I arrived at his house and, I sat down on his stairs and announced, ‘Well, here I am.’ They had no idea of what kind of bird had just landed in their nest.”

____________________

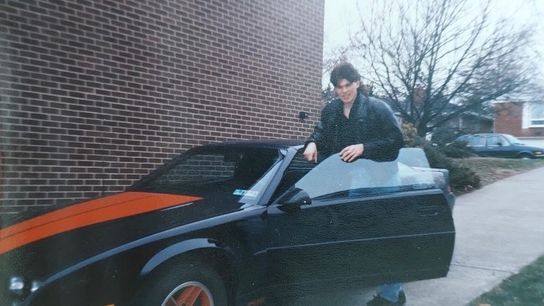

RICK NEMEC

Jaromir Jagr brought his Camaro to Rick Nemec's house to see in 1991.

Placing out-of-town players in the homes of billet families is a generations-old practice, but until the early 1980s it was one mostly reserved for the junior-hockey ranks. The Penguins famously changed that when then-general manager Ed Johnston asked a prominent local businessman if he would open his Mount Lebanon home to Mario Lemieux.

The Penguins didn’t want the No. 1 overall pick in the 1984 draft living alone in a downtown apartment. The French-speaking Lemieux was under enormous pressure, and he had his share of off-ice obstacles to overcome. But the future franchise savior thrived in the home of Tom and Nancy Mathews for one year and, two decades later, he extended the same offer to Sidney Crosby, who lived with the Lemieuxs.

In 1990, Patrick opted for a similar arrangement for Jagr, who the Penguins selected No. 5 overall. Everyone around the team understood the challenges facing the 18-year-old's immediate development.

“Think about the culture shock,” said former beat writer Tom McMillan, who recently retired from his post as the franchise’s vice president of communications. “Jagr doesn’t speak a word of English. There are no other Czechs on the team at first. He’s coming from a communist country where there always were shortages and very little freedom.”

Patrick invited a handful of local families into his home to meet with the Jagrs, including several who had emigrated from Czechoslovakia. It was a form of billet speed dating.

Jagr took an instant liking to the Nemecs. He appreciated that Stefan, a metallurgist in the steel industry, and his brother Josef had taken the risk to leave home and start a new life in America after the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies crushed the Prague Spring protests of 1968.

The Jagr family had a fierce independent streak. His grandfather was a character right out of a Steve Earle ballad, a fearless freedom-loving farmer who chose a jail cell over surrendering his land to the communists without a fight. Jagr wore the No. 68 in honor of the Prague Spring. As a kid, he carried a picture of Ronald Reagan even as his teachers admonished him for it. He later spoke to Reagan by phone, according to Jagr’s autobiography.

Unlike his friend and future Penguins teammate Petr Nedved, he didn’t have to defect. The Velvet Revolution of 1989 brought an end to authoritarian rule in his homeland just as the Berlin Wall was coming down in East Germany.

“You could tell how much he liked the West,” said Rick Nemec, the nephew of Stefan and Olga. “(Jagr’s) mother invited us to their home in Kladno in the 1990s. In his bedroom, there was an exercise bike and there were two posters. One poster was a hockey poster. The other poster had a picture of the Bruce Springsteen album cover with the American flag and the (red handkerchief) in his back pocket.”

Rick Nemec was 15 when Jagr arrived in Pittsburgh. The young Penguins fan couldn’t believe his good fortune. His family scored tickets to Stanley Cup playoff games courtesy of Jagr’s mother, Anna.

The budding star autographed sticks and a helmet to be auctioned off at his high school. Rick watched in awe as Jagr used’s his uncle’s stove to bend the blades of his sticks. When Jagr outgrew the acid-washed jean jacket he bought at the Ross Park Mall —a KDKA television crew had accompanied him on the shopping spree — he gave the jacket to Rick.

TOM REED / DKPS

Rick Nemec displays the jean jacket that Jaromir Jagr gave him.

“He was always so fun to be around,” Rick recalled. “I had a hockey goal and a baseball glove and I would stand in the net while he was shooting whiffle balls. He’s scoring at will and making fun of me the whole time. He kept putting it up over my shoulder. He missed the net once and shattered a single-pane glass window in our garage door. He did this with a whiffle ball.”

____________________

Bourque realizes most fans think only of the happy times when recalling Jagr’s early years in Pittsburgh. The infectious smile. The love of Kit-Kat bars. His hilarious weather reports on WDVE. The catalog of brilliant goals.

There were plenty of hardships, as well, especially in his first few months.

When the club went to Vail, Colo., for its 1990 training camp, coaches could not communicate with Jagr. The hockey prodigy with the bulging thighs might have been a student of the game, but his English lessons weren’t yielding results in the classroom. Johnson did a radio interview in Vail and asked if any Czech-speaking fans could come to the rink and act as an interpreter. A construction worker answered the call and stood on the ice conversing with Johnson and Jagr.

“Jaromir was naive, and that’s not a word we often associate with him,” Bourque said. “At times, I think he was overwhelmed. We would remind him to keep his head up, but there were times when he would come through the middle of the ice and just get smoked.”

Bourque recalls tears in the dressing room and on the ice.

“Jags comes to the bench and he’s crying, but it’s not a typical cry,” he said. “It was like he was hyperventilating at the same time. I’m sitting next to Jags, and Kevin Stevens is down the bench by the door and Kevin stands up and says, ‘Is he f**king crying? Someone shut that f**king baby up.’”

RICK NEMEC

Jaromir Jagr heats up a stick blade before a Nemec family dinner.

The Nemecs did what they could to combat the obvious homesickness, particularly during spells when Anna went back to Kladno. Olga cooked him native dishes: breaded pork chops, sauerkraut with roast beef and pureed vegetable gravy, steamed dumplings.

But as Jagr’s play deteriorated, he grew sullen and, at times, confrontational with the Nemecs. There were arguments over the volume of his music and his perceived lack of personal freedom. These were the days before he owned a car. The Penguins allowed former amateur hockey development director George Kirk to squire him back and forth to Mellon Arena, but that was about it.

Stefan and Olga, who had two grown children living outside the area, remained unyielding in the face of Jagr’s protests, doing what they thought was best to protect the teenager.

“The Nemecs helped me immeasurably and took care of me like I was their own son, but you can’t replace your own parents, after all,” Jagr writes. “I started saying I wanted to go home. Mr. Nemec eventually got fed up enough with me that he answered, ‘OK, just tell me when you are leaving and I will drive you to the airport.’

“One time I told them I felt like I was in prison ... I yelled at Mr. Nemec, ‘You can’t tell me what to do, you’re not my father!’ To which he replied with icy calm: ‘Be glad.’”

____________________

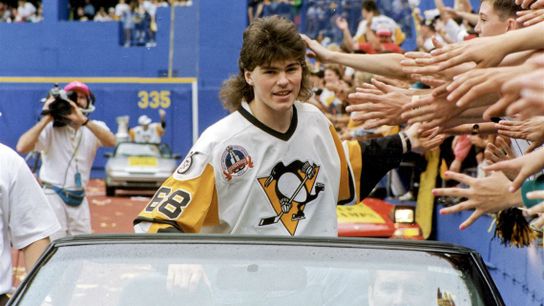

GETTY

Jaromir Jagr rides in a 1992 Stanley Cup parade through Three Rivers Stadium.

Helena Nemec didn’t need to know the first thing about sports psychology to diagnose the root cause of Jagr’s 16-game goalless drought that stretched into mid-December of his rookie season.

“He was lonely,” said Josef Nemec’s wife of 50 years. “Jagr played tennis and ping-pong all the time back home with friends, but here he was just sitting in Stefan’s house. He was miserable.”

The Penguins took a major step in addressing the issue by trading for Flames veteran forward and fellow Czech countryman Jiri Hrdina. The center made valuable contributions in two championship runs, but his biggest influence came off the ice in helping Jagr adjust to life in the NHL and America.

Hrdina already was a Stanley Cup winner and a legend on the national team. His presence coincided with a remarkable turnaround in Jagr’s production. In the 33 games prior to Hrdina’s arrival, Jagr registered seven goals and five assists. In the remaining 47 regular-season games, he recorded 20 goals and 25 assists.

“The trade for Jiri is the biggest trade that people never talk about,” Bourque said.

Lemieux returned to the lineup after missing much of the regular season recovering from back surgery. The team acquired Ron Francis and Ulf Samuelsson in a franchise-altering deadline deal.

Around the Nemec house, Jagr was in high spirits. He promised the family he would take everyone to dinner if the Penguins won the Cup. Meanwhile, Josef was sending VHS tapes of every game back to Kladno so the Jagrs could follow their son’s progress.

And then came the article. The family had allowed a local reporter into their home to write a behind-the-scenes story. It was a complimentary and well-received piece, but it also named the family and included the suburb where Jagr was lodging.

He was already becoming a fan favorite with his flashy play and good looks. Now, the supporters who wanted to get closer to Jagr knew exactly where to find him.

“Once fans find out where he lived, it was like highway in front of my brother’s house,” Josef said. “People standing in front of the house. Ringing the bell. Nobody would answer, but they kept ringing. Sometime in the evening, they would turn their cars around and shine their lights into the windows.”

Rick recalls some of the “inappropriate” fan mail Jagr received from women at his uncle’s residence. But Stefan held firm with an assist from Jagr’s driver.

“People showing up at the house went over the line in my opinion,” Kirk said. “I tried to be direct and say, ‘It’s wrong for you guys to be doing this.’”

In his autobiography, Jagr writes that Kirk had to sometimes outrun overzealous fans in his metallic blue Suzuki Samurai. Kirk also had to repeatedly tell Jagr he couldn’t take his stick-shift sports car out for a spin.

Jagr acknowledges the emotional toll his season with the Nemecs took on the host family. The only money they received from the Penguins was to cover the rent.

“(They) must have breathed a huge sigh of relief when they finally got me out of their hair,” Jagr writes. “I think they aged five years in my one-year stay.”

Jagr made good on his vow to take the Nemecs to dinner after the Penguins won their first Cup. That night gave the family a glimpse into Jagr’s future.

“My brother said, ‘Oh, that was a mistake,’” Josef recalled. “He said, ‘As soon he show up, the bar is full of girls. I didn’t know what to do. We went home early.’”

____________________

RICK NEMEC

Jaromir Jagr surrounded by family and friends in the Nemec household. That's Martin Straka sitting next to him.

A year later, Rick Nemec was outside his home when he saw a black Camaro pull into his driveway with Jagr behind the wheel.

“He is trying to tell me how I can buy one and I’m like, ‘Jaromir, I wash dishes in a restaurant part-time.’” Rick said.

Jagr spent the 1991-92 season living with a family in Bridgeville. The change in residence allowed him to enjoy the customs of American-born billets and it afforded him more freedom in his daily routine.

It all went swimmingly except for the highway patrolmen who had to chase down the speeding Camaro and for the police in charge of collecting fines.

“I rode with him one time,” Bourque said. “He asked me to throw something in his glove box. When I opened it, there must have been 20 tickets in there. He’d get the tickets from the cops and shove them in there the way we would shove in old mail or fliers from Levin Furniture.”

After winning a second Cup, Jagr thought it was time to get a place of his own. Just as he was about to buy a house, he got an offer he couldn’t refuse. Stefan and Olga Nemec were temporarily relocating to Lima, Oh., for Stefan’s job. Did the Jagrs want to live in their vacant home for two years?

Jagr and his mother gratefully accepted. Before long, younger Czech-born players such as Martin Straka joined the Penguins. These were some of Jagr’s happiest days in Pittsburgh.

He eventually bought a home in Upper St. Clair before an acrimonious divorce with the Penguins saw him traded to the Capitals in 2001. Jagr’s legacy in Pittsburgh is complicated and his departure led some fans to booing his returns to town, especially after he joined the rival Flyers during the 2011-12 season.

One bridge he never burned was with the Nemecs. To celebrate the millennium, Jagr flew the family to Atlantic City and put them up in a hotel.

Though Jagr hasn’t played in the NHL since 2017 with Calgary, he still owns his house in Upper St. Clair. Josef and Helena are the caretakers and they speak frequently with Jagr’s mother.

Stefan, 89, and Olga, 82, live in a Missouri retirement community, where their children relocated them to be closer. Both are in declining health, and were unable to be interviewed.

A legend from the very beginning... and still making hockey magic today at age 50! Happy birthday, @68Jagr! 🥳 pic.twitter.com/99aIBiAy2u

— Pittsburgh Penguins (@penguins) February 15, 2022

Jagr has never forgotten what the family did for him during his chaotic and triumphant rookie season.

“They were incredibly nice to me and helped me out with everything, right down to my financial accounts,” Jagr writes. “(I remember telling) the Nemecs I wasn’t going to (file my income tax forms). Boy did they go crazy then. ‘They will put you in jail!’ Without their help, I would have been completely lost.”

When Jagr finally retires from the Czech team he owns, the Penguins icon will be enshrined in the Hockey Hall of Fame. There’s also another honor awaiting him — seeing his No. 68 raised to the rafters at PPG Paints Arena.

“He thought everyone hated him here because he got booed all the time after he left,” Bourque said recalling a conversation he had with Jagr during a visit to Kladno. “I laid it all out for him. I said, ‘On that night, everyone will cheer you, everyone is going to appreciate what you did for the Pittsburgh Penguins. It’s all going to come together.’ Jags’ eyes got really wide.”

Tickets for Jagr’s jersey retirement ceremony will be hard to obtain, but the Nemecs will find a way to be there. After all, they have pretty good connections.