COLUMBUS, Ohio — John “Frenchy” Fuqua still owns the white buccaneer boots he wore during the televised locker room “dress-offs,” the ones that were Myron Cope inspired and Chuck Noll approved.

The former Steelers running back also has the famous skin-tight lavender jumpsuit, the pink floor-length cape and the glass cane, all tucked away for safe keeping in his Detroit home.

When the mood strikes, the 74-year-old Fuqua will entertain guests by sauntering down the steps in one of his two pairs of platform shoes with goldfish in the plexiglass heels.

“It still feels good to occasionally be 6-foot-3 instead of 5-foot-11,” Fuqua said. “But then, I take them right off because I don’t want to break my neck.”

During his seven seasons with the Steelers (1970-76), Fuqua was such a fashionista that he penned an angry letter to the editor of Esquire magazine protesting his 1972 exclusion from its “Ten Best-Dressed Jocks,” edition.

Fifty years later, Fuqua retains the swagger and loquaciousness that made him popular with teammates and “Frenchy’s Foreign Legion” on the way to winning the Steelers first two Super Bowl titles. However, he’s no longer a haberdasher’s delight.

“You know what my favorite attire is now,” Fuqua said rhetorically. “My pajamas and my slippers.”

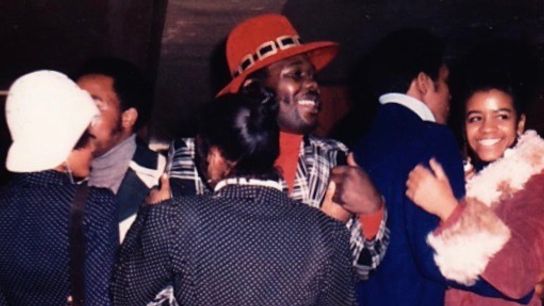

Steelers RB Frenchy Fuqua dressed like a vampire pimp at Three Rivers Stadium may be the apex of Western civilization pic.twitter.com/Vekp2ETPid

— Super 70s Sports (@Super70sSports) May 31, 2015

Monday afternoon, the man who called himself a “French Count” was home sipping Jack Daniels, cleaning the basement and ordering chicken wings and chili in advance of his Super Bowl party.

“I die a little when football season ends,” he admitted, “but I live life to the max.”

Fuqua remains relevant in ways few former pro athletes from his era can fathom. A central figure in the greatest and most controversial play in NFL history, he has turned the Immaculate Reception into the sport world’s longest-running side hustle.

For years, he has featured at banquets, Steelers tailgate parties and Rotary Clubs, relieving the miraculous play that delivered the team’s first-ever playoff win without revealing the answer to the mystery which celebrates its 50th anniversary on Dec. 23.

Fuqua estimates he does 20-plus appearances a year. His current rates vary, and the can run up to $2,500, a fee that entitles an audience to “the works.”

“I got the gift of gab,” Fuqua said. “I bullshit. I tell the truth and I lie, but I consider that part of the business.”

Former Steelers quarterback Terry Hanratty marvels at the cottage industry his old friend has helped create around the Immaculate Reception. Franco Harris caught the ball that ricocheted to him after a collision involving Fuqua and Jack Tatum, and he ran it to the end zone for a 13-7 win over the Raiders. Yet it’s Fuqua who is the biggest benefactor.

“Nobody has made more money off one play in the history of mankind,” Hanratty said laughing. “And he still continues to do it. He’s not giving that up, and I don’t blame him.”

In an age when so many pro athletes go broke despite making millions during their playing days, Fuqua’s story is an educational one. Beyond the flashy threads and colorful quips is a former Steeler who understood the value of hard work, common sense and marketing.

You can ask him all about it during one of the many Immaculate Reception functions he’s bound to attend in the coming year.

____________________

STEELERS

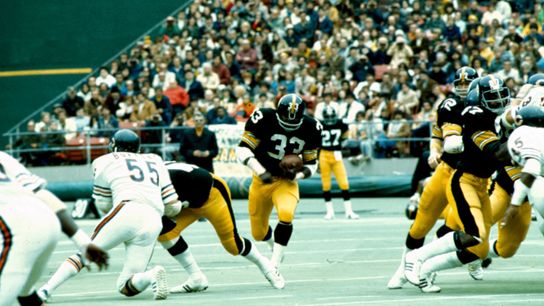

John "Frenchy" Fuqua was the Steelers' leading rusher in 1970 and 1971.

Joe Gordon, the legendary Steelers media relations guru, isn’t surprised to learn that Fuqua’s home in the historic Rosedale Park district of Detroit is paid off. That he has no car payments or creditors looking to lower a financial boom.

Even before the Immaculate Reception and two Super Bowl rings, the enterprising Fuqua was looking to make extra cash. He was, after all, an 11th-round draft of the Giants in 1969 when signing bonuses for players of his ilk amounted to an extravagant night out on the South Side.

“After practice, Frenchy would come in my office and say, ‘You got anything for me tonight?’” Gordon said. “At the time, the players would get $50 or $100 for an appearance. If I had something five nights in a row, he’d do it because he loved interacting with people. He would put on a great show and he was in demand."

Fuqua viewed every gathering as a potential earning opportunity — even the Steelers’ poker games they played on the road.

“You had to keep three or four eyes on Frenchy because there were always six aces in the deck when he played, and two of them were under his legs,” Hanratty recalled.

Fuqua said he bought only one new vehicle, a Lincoln Town Car, during his seven-year run with the Steelers. After establishing his reputation for haute couture, Pittsburgh boutiques gave Fuqua suits and apparel, he said, for the promise that he’d don them on game days or special events.

“Myron would promote what I was going to wear,” Fuqua said. “He was very influential in teaching me how to market myself.”

The NFL has never approached him about speaking to young players in regards to how to manage their earnings, but Fuqua has strong opinions on the subject.

Don’t assume you will play at least three years and draw a league pension. Don’t buy expensive vehicles for relatives while on a rookie contract. Don’t be wasteful with your signing bonus. Be mindful of the approximately 30 years between the end of your playing career and the time you can tap into your pension and Social Security.

“The NFL is a stepping stone for the rest of your life,” Fuqua said. “Yeah, it’s a dream, but you can wake up at any moment. I would tell these guys to take the burden off their future, not their present.”

Like many NFL players of his era, he worked summer jobs. While the Steelers’ stars of the 1970s were busy winning two more Super Bowls, Fuqua was retired and home recruiting paper boys for the Detroit News. He still can recite his pitch:

“Good morning, students, my name is John “Frenchy” Fuqua, former running back with the Pittsburgh Steelers, currently employed as Carrier Recruitment Supervisor at the Detroit News. Some of you may or may not know at this time every year people like myself and our competitor, the Detroit Free Press, come out looking for the backbone of our business. And that’s you, the carrier. For those who are interested, we currently have routes in your area available paying from $25 to $38 a week.”

Fuqua spent more than two decades in the business. There were no lavish signing bonuses in his second pro career, but one of the perks was marrying his secretary, Shree, after his first wife, Doris, had died.

Among his proudest memories are seeing all five children earn their college degrees. His monthly income from his NFL and newspaper pensions totals about $8,000, he said. And that’s not factoring in the money he makes in appearance fees.

“I’d tell these players to take $1,000 from their bonus and you and your girlfriend go out and have a ball for a weekend,” Fuqua said. “After that, save every penny you get because it won’t last forever.”

____________________

JOHN FUQUA FACEBOOK

John "Frenchy" Fuqua never skimped on style, especially out on the town.

Former offensive lineman Jon Kolb grew up in a small town in Oklahoma that had no traffic lights and five Baptist churches. He stayed home to play his college ball at Oklahoma State before the Steelers used a third-round pick to draft him in 1969.

Culture shock doesn’t begin to describe his early years in Pittsburgh. The locker room teemed with electric personalities. Roy Jefferson. Joe Greene. L.C. Greenwood. Ernie Holmes. Kolb’s earliest memory of Fuqua with the Steelers was a decibel-splitting one at training camp.

“Fenchy would spend hours in his room listening to the song ‘Back Stabbers’ (by the O’Jays) over and over again until 11 o’clock,” Kolb recalled. “I can remember looking out at the cemetery thinking there were probably dead people walking around because they couldn’t sleep.”

Fuqua’s off-field personality belied his serious approach to his craft. Kolb and Hanratty termed him a “complete back.”

Acquired in a trade from the Giants, he led the Steelers in rushing during the 1970 and 1971 seasons. His 218-yard performance against the Eagles in 1970 stood as the single-game franchise record until Willie Parker eclipsed it in 2006 with a 223-yard effort against the Browns.

Fuqua, who played at 200 pounds, was capable of catching passes and blocking defenders who outweighed him by 30 and 40 pounds. The arrival of Harris in 1972 significantly cut into Fuqua’s rushing attempts, but he continued to contribute in other facets.

“Franco was a great runner, but he wasn’t a great blocker,” Kolb said. “He used to say, ‘I’m going to sting that (opponent),' but he had a habit of closing his eyes and running into one of his teammates. That’s how Franco got the nickname, ‘Sting Bee.’”

Fuqua finished his eight-year career with 3,031 yards rushing and 1,247 yards receiving. He also brought invaluable intangibles to the Steelers with his infectious personality. He kept teammates loose with his antics, which helped the club during the grind of a long season.

“Frenchy and L.C. were the kings of the locker room,” Kolb said.

Fuqua bought his first pair of bell-bottom jeans in New York. But it was his lavender jumpsuit and pink cape that caught everyone’s eye.

“I called it my Caveman jumpsuit,” Fuqua said. “It was unique. It was different. It was preposterous, really. One our safeties, Chuck Beatty, didn’t like the attention I was getting. He said, ‘I’m the best dresser on this team by far.’ So Myron sets up a dress-off. L.C. was my main rival, but even (Terry) Bradshaw got into the act with his cowboy hat.”

Let’s stop for a moment and ponder the NFL’s buttoned-up culture of present day.

What coach would allow a local TV reporter to bring a camera crew into the locker room to film an annual fashion contest? Noll might have been the ultimate stone face, but he recognized the importance of team camaraderie, especially on a burgeoning juggernaut.

“Myron would conduct these dress-offs, and it was kind of fixed so you knew Frenchy would win regardless of who he was competing against,” Gordon said. “It was popular among his teammates and it pulled everyone together. It kept things in perspective and reminded you it wasn’t always life and death. Myron would promote the dress-offs a week in advance on WTAE-TV. There was great anticipation and they would do it in the dressing room. Myron.”

Fuqua bought a “Pancho Villa” sombrero in California for one of the contests. The showstopper, however, came in the final year of the dress-offs.

“I’m thinking to myself, ‘How am I going to top my last outfit,” Fuqua said. “That’s when this guy told me, ‘I got just what you need, something that’s going to blow their minds — a pair of goldfish shoes.’ I said, ‘I’ll take ‘em.’”

Hanratty recalls that adding marine life to Fuqua’s fashionable footwear involved some trial and error.

“Frenchy couldn’t figure out why the goldfish kept dying,” Hanratty recalled. ‘I’m like, ‘Frenchy they need air to live.’”

Five decades later, no big sporting event is complete without images of star players walking into stadiums. Fashion designers pay big money for athletes to rep their brands. Internet sites create power rankings for the best and most outlandish looks.

Fuqua was 50 years ahead of his time in terms of branding. He even dabbled in poetry with one of his works published in the New York Times:

“I swam the ocean and didn't get wet. A mountain fell on me and I ain't dead yet. Horses and elephants trampled my hide. A cobra bit me and crawled off and died. I hitchhiked on lightning, rode with thunder. Made people wonder. Whoa, whoa. Yes, I'm a man of some ability, with much more agility. Often imitated, but never duplicated.”

____________________

GETTY

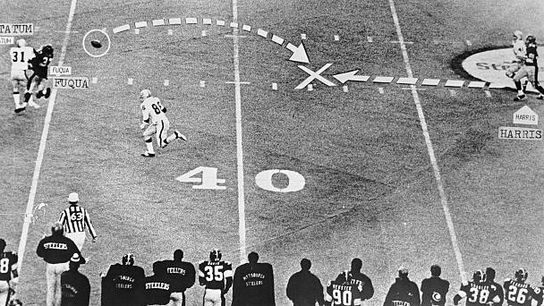

The force of the Jack Tatum-John "Frenchy" Fuqua collision caused the football to carom seven yards.

Men who make history often find themselves in the right place at the right time. And so it went with Fuqua in the dying moments of the 1972 divisional playoff game at Three Rivers Stadium.

Fourth down-and-10. No timeouts remaining, 22 seconds left on the clock, the Steelers trailing by a point. Ball on the Pittsburgh 40-yard line.

Bradshaw eluded a heavy rush and fired the ball down the middle of the field to the Raiders' 35, where Fuqua and Tatum violently collided.

“I knew I was going to have to take a blow,” Fuqua said. “I could hear the Assassin’s footsteps, I could hear him breathing. The first thing I wanted to do was catch the ball, of course. The second thing was to make sure Tatum didn’t catch it. We were both running to a point.”

The ball caromed seven yards back toward the line of scrimmage, where an alert Harris caught it just before it hit the ground. He galloped to the end zone, while stunned players and fans tried to process what they has just witnessed.

December 23, 1972

— Old Time Football 🏈 (@Ol_TimeFootball) December 23, 2021

The Immaculate Reception#Steelers pic.twitter.com/9h1qpWVccb

Mayhem ensued. Fans rushed the field. The officials huddled in a dugout for 15 minutes before ruling it a touchdown.

The Raiders vehemently protested the call. Conspiracy theories continue unabated to this day. Some believe the ball hit the ground before Harris caught it. Others think Harris was aided by an illegal block on his run to the end zone.

But the biggest controversy surrounds whether the pass struck Tatum or Fuqua. By the rules of the day, the receiving team could not touch a pass twice in succession. If the ball had ricocheted off Fuqua, the completion should not have counted.

Video of the play remains inconclusive. It’s been dubbed the “Zupruder film of pro football.” In the locker room, Fuqua was told by the late Art Rooney to keep quiet about what happened.

There’s no telling how much money that piece of advice has made Fuqua over the years.

“I don’t have to cash my pension checks,” he said jokingly.

Fuqua has milked the mystery for all that it’s worth. He and Tatum, who died in 2010, reportedly appeared together at speaking engagements to keep the debate brewing. Within the past three years, the Immaculate Reception has been named the NFL’s greatest play by a media panel and through a fan vote.

“That ball bounced off Tatum,” Hanratty said. “Frenchy is running sideways at the time of the collision. There’s no way it goes back that far if it hits Frenchy.”

“In my opinion, Frenchy doesn’t know what the hell happened on that play,” Gordon said. “He got hammered by Tatum and he was on the ground when everything happened.”

Two things are certain. The Immaculate Reception launched a decade of dominance for the Steelers and fans of the Silver and Black have never gotten over the perceived injustice.

“We started playing some flag football games when I was like 40-years-old,” said Hanratty, 74. “It’s 7-on-7 and everyone’s in shorts. We go out to Oakland and play on a night when the Giants are playing a home playoff game. There’s 30,000 people in this stadium and the Raiders fans are booing the shit out of us. I’m like, ‘Can you believe these f***ers are still booing us?’”

All the resentment and lingering intrigue keep Fuqua on the road about 20 times a year.

A master storyteller, Fuqua builds the suspense and allows his audience to believe he’s finally going to reveal the secret. He never does. Sometimes, he works Shree into the act, having her sit in the crowd and ring his cell phone pretending to be Roger Goodell as in this video from the NFL Network:

Bradshaw and Harris are enshrined in Canton. Tatum died as one of the most feared hitters in football. And yet it’s Fuqua — the least known among the four principle characters — the one who Tatum planted into the Three Rivers Stadium turf on Dec. 23, 1972 who’s still cashing the checks. Still, sipping on his Jack and waiting by his phone for the next engagement.

“My thing is the Immaculate Reception,” Fuqua said. “It’s the greatest play in NFL history, and that’s why I’m still out there telling my stories.”

Maybe in this golden anniversary year, the Mad Frenchman finally comes clean. He walks into the closet and grabs his white musketeer hat with red, white and purple ostrich plumes, and sets the record straight.

Gordon laughs at the thought.

“Frenchy will die with his secret,” Gordon said. “He will take it with him to his grave.”