Back in 2013, the Pirates banked on the infield shift to be the catalyst for their turnaround.

10 years later, they're betting on players who could benefit now that the shift rules are changing.

On Friday, the Pirates made their largest free agent signing of the Ben Cherington era, inking veteran first baseman Carlos Santana to a one-year, $6.7 million deal. Earlier this month, they traded for Ji-Man Choi from the Rays, giving them a couple veteran options for first base and designated hitter, two clear areas of need.

Both hitters posted roughly average offensive results in 2022 -- Santana had a .692 OPS and a 100 OPS+, while Choi had a .729 OPS and 114 OPS+ -- though their batted ball peripherals were more flattering and suggested they were a bit unlucky. Santana had a .202 batting average and .376 slugging percentage compared to an expected .253 average and .438 slugging percentage, according to Baseball Savant's batted ball data. Choi's expected slugging percentage was 25 points higher than his actual rate (.388 to .413).

Banning -- well, weakening -- the shift could be good way to get those extra hits to bridge the gap between actual and expected results. Last year, Santana was shifted in 98.3% of his plate appearances when he batted left-handed, the highest rate in all of baseball. Choi was shifted in 83.9% of his plate appearances, the 23rd-highest rate out of the 307 hitters across baseball who had at least 250 plate appearances.

It's reasonable to expect the league will see an uptick in offense because of the new shift rules, but how big a boost could these two hitters get from the change?

While aggressive shifts are banned, teams will still strategically place their infielders. The rule reads that teams must have two infielders on both sides of second base, but that doesn't force them to have a traditional alignment. In many shifts against left-handers, the shortstop would play up the middle and the third baseman would move over to the traditional shortstop spot. Teams can still more or less do that, just moving the shortstop a foot or two towards the left side of the infield.

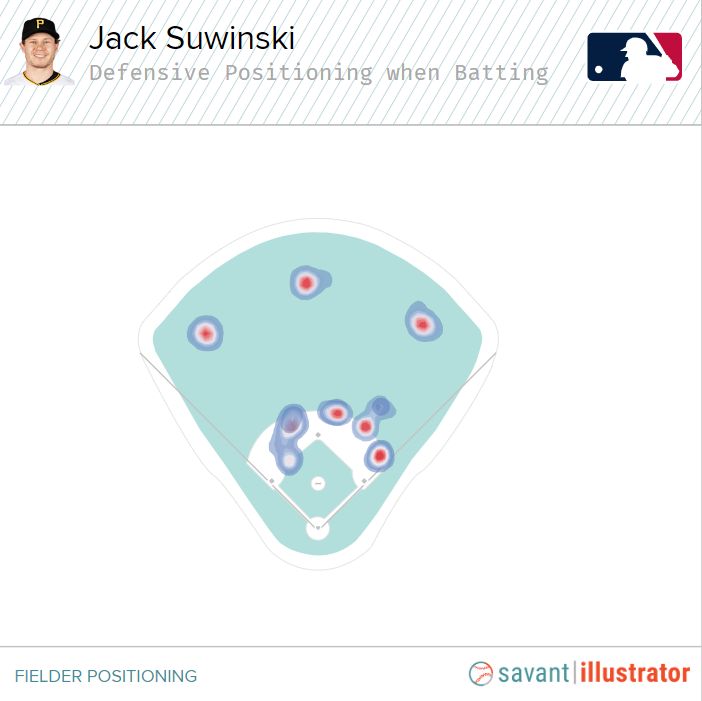

Take Jack Suwinski, for example. He saw a shift in 71.2% of his plate appearances last year, but they weren't the most aggressive shifts. The shortstop and third baseman usually just moved over a couple steps from where they would normally play.

Baseball Savant can chart where fielders were positioned with nobody on base. Those red dots indicate where the fielder set up the most, while blue shows different areas where they were positioned at one point. For Suwinski, the infielders were almost always on the dirt:

BASEBALL SAVANT

For hitters who saw these types of shifts in 2022, they probably won't see many extra hits because of the rules in 2023. It will just force the shortstop to move a couple steps to their right.

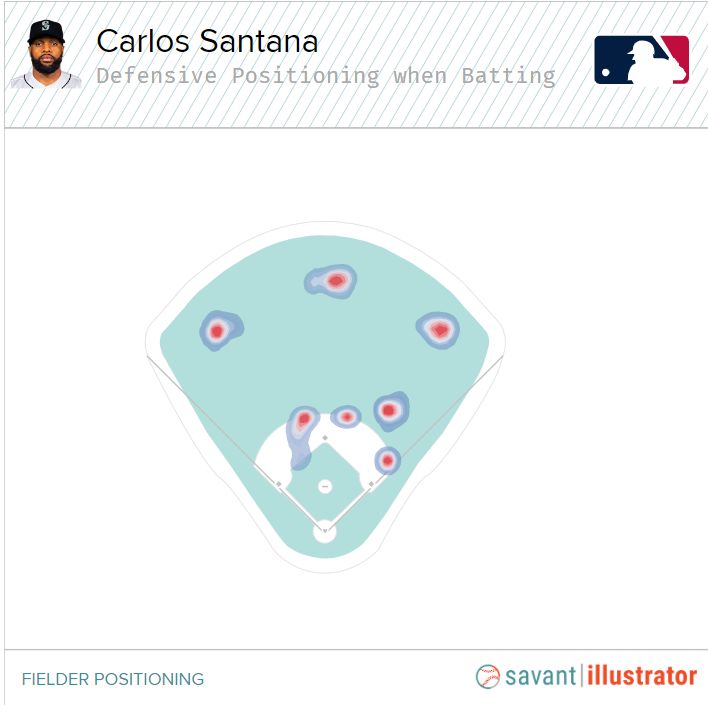

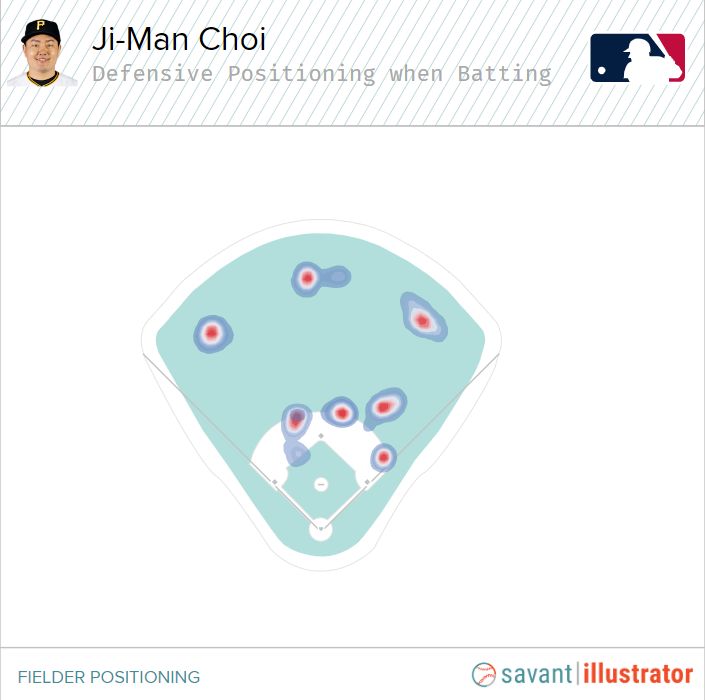

What this rule change does is get rid of the aggressive shift, like one where an infielder plays on the grass in shallow right field. Those shifts would effectively vacate the left side of the infield, but leave barely any space to sneak a single through the right-hand side.

These are the types of shifts Santana and Choi saw the most frequently last year. Here's where infielders set up against Santana:

BASEBALL SAVANT

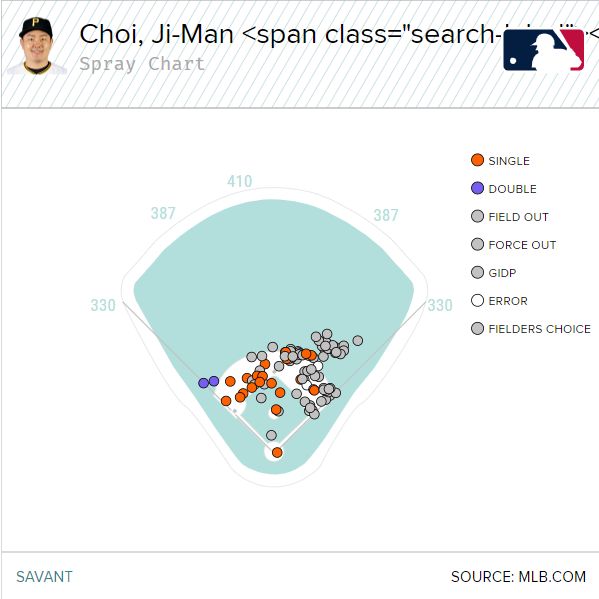

And now Choi:

BASEBALL SAVANT

In a normal at-bat, both Santana and Choi saw only three fielders positioned on the dirt. It stands to reason that forcing that fourth infielder back to a more traditional position would help them.

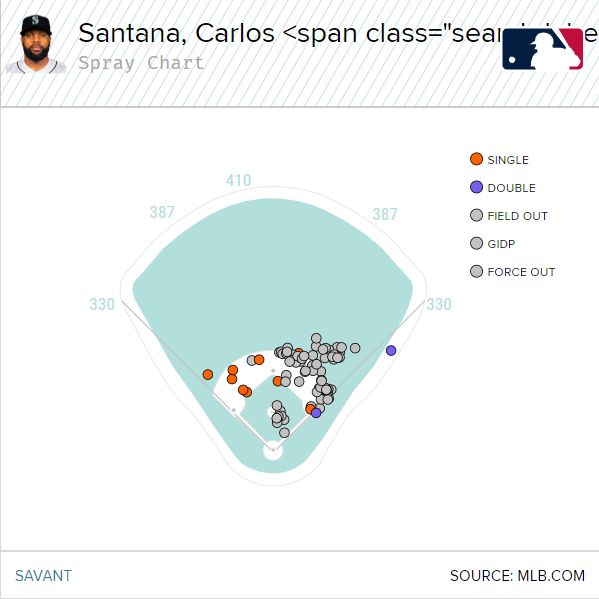

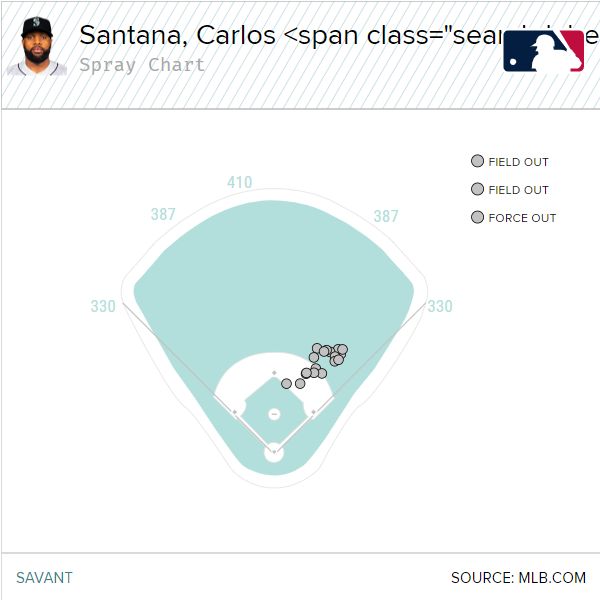

Santana's ground ball spray chart last year shows why he was so heavily shifted. He only had 11 ground ball hits last year, and five were to the opposite field:

BASEBALL SAVANT

He was shifted so often because the shift was so effective. He had a .177 batting average on balls in play (BABIP) as a left-handed hitter.

In the live ball era (since 1920), Stathead tracks 5,429 individual seasons where a left-handed or switch hitter had at least 350 plate appearances against a right-handed pitcher. Of those 5,429 seasons, Santana's .177 BABIP is the worst. You can call it unlucky. You can say the shifts were really that good. But there's no other way to slice it: Santana had a historically-bad BABIP.

The new shift rules should create more hits. It just not might be as many as some expect.

Let's look at launch direction. Not angle, which measures lift off the bat, but direction, which is the direction it goes to the field. A ball with a 0 degree launch direction is perfectly up the middle, where if it's pulled it has a positive launch direction and a negative if it's hit to the opposite field.

Santana hit 79 ground balls that had a launch direction of -5 degrees or higher, meaning his pulled batted balls or the ones roughly up the middle. Here is how they broke down by angle:

-5 to 5 degree: 9 batted balls

6 to 15 degrees: 13 batted balls

16 to 25 degrees: 15 batted balls

26 to 35 degrees: 20 batted balls

36 to 45 degrees: 15 batted balls

46+ degrees: 7 batted balls

10 degrees of launch angle is a very rough estimate of what a fielder can cover. For example, here are Santana's batted balls with a 26-35 degree launch direction:

BASEBALL SAVANT

That's a reasonable area for a second baseman to cover. If you put that shortstop just a hair on the third base side of second, 44 of those 78 ground balls fall into three ranges of 10 degrees (-5 through 5, 26-35, 36-45). Last year, Santana went 3-for-44 on ground balls with those launch directions. Infielders don't have to be positioned exactly here, but in a rough first look, half of these ground balls should be fielded without much issue.

There's no guarantee those other 35 batted balls are going to be hits either. It could be softly hit, the fielder could have shaded a bit more that way or maybe the third baseman makes a play on a ball the other way. But even with the new positioning restrictions in place, we could have taken away most of Santana's batted ball hot spots from last season.

Choi, on the other hand, made an effort to try to beat those shifts last year, giving him a .238 BABIP on ground balls while the infield was shifting. That's actually a pretty decent average:

BASEBALL SAVANT

Bringing an infielder back to the third base side of second could hurt this strategy. He no longer will have half of the diamond to roll the ball through. Sure, he could lean into trying to pull it more, and this should still help him out. But a soft shift might be roughly as effective as an aggressive shift once those opposite field base hits are taken away. He could just be replacing some singles to left with singles to right.

The new shift rules should create more hits for Santana and Choi, but teams should still be able to position their infielders in a way where they can get to the majority of their batted balls. There could be other consequences of the rule change. Instead of trying to poke one to left, Choi could let one rip instead, and it might go for a home run. There will be trickle down effects.

But as long as teams can still have some freedom of where they can put their infielders, left-handed hitters are still going to have to try to overcome some form of shift.