ST. LOUIS -- “It’s been documented so much, you wonder what’s left."

Al Oliver has a point. The topic of discussion was Roberto Clemente and his 3,000th hit, perhaps the greatest individual achievement ever accomplished by a player in a Pirates uniform. That historic moment on that Saturday afternoon at Three Rivers Stadium occurred exactly 50 years ago today: Sept. 30, 1972.

50 years is plenty of time to recount a career and one of a Hall of Famer's crowning moments on a baseball diamond. There are books, articles, a whole museum in Lawrenceville. The 2010 film Chasing 3000 is a fictional road trip movie where driving across country to watch Clemente go for his legendary hit is the inspiration for the trek.

To put it succinctly, a lot of ground has already been covered.

"Every year there’s a documentary, there’s a film, there’s a playground named after him, a park," Steve Blass said. "He’s unique in that way.”

It's why the events of that September are so well-known, even if the announced attendance at Three Rivers was just 13,117 that afternoon. Even if it wasn't the top story of every local newspaper's sports page. Even if he almost had the 3,000th hit the night before. For a figure as beloved now in Pittsburgh as Clemente, those periphery stories get swapped amongst Pirate fans.

Stories are what makes a player or person into an icon. Even though he collected 3,000 hits, a dozen Gold Gloves, multiple World Series rings and just about every individual accomplishment one can achieve on the diamond over an 18-year career in Pittsburgh, the legacy of Clemente is almost always as a humanitarian and a ballplayer, if not just the former. Friday is a rare day where he is recognized and celebrated as a player first.

"It's a special day," Roberto Clemente Jr. said before embarking on a trip to St. Louis to attend the Pirates-Cardinals game on the anniversary. "I can’t believe it’s been half a century and his legacy is that strong."

____________________

MORRIS BERMAN / GETTY

Roberto Clemente talks to the media after getting his 3,000th hit.

Going into 1972, the prospect of Clemente reaching the 3,000 hit plateau was more or less a given in the clubhouse. He entered that year just 118 hits away. Oliver thought he would reach that with plenty of time to spare.

“People weren’t speculating he was going to get 3,000," Bob Smizik, the Pirates beat reporter for The Pittsburgh Press, told me. "It was a pretty certain deal.”

The rest of the league seemed to agree. In an interview with Richie Ashburn during the 1971 All-Star Game, Clemente was asked about getting No. 3,000 the following year.

"You never know because God tells you how long you’re going to be here," Clemente responded after a moment to collect his thoughts. "So you never know what can happen tomorrow.”

“It was kind of prophetic that he would say that," Oliver said.

Clemente of course reached the hit mark, but nobody expected it to happen in late September. The first few games of the season were lost to a player strike. An ankle injury would limit him to just one start from July 10 to Aug. 21. Going into that final month, Clemente was 30 hits away from the milestone. He recorded a .333 batting average over the final month of his career to reach the mark, a feat few hitters could accomplish at age 38 coming off of injury.

“The man upstairs wasn’t going to allow him not to get 3,000 hits," Oliver said.

Depending on who you asked, or who was at the ballpark on Sept. 29, he could have reached the plateau a day earlier.

“We thought he hit it the night before," Blass said.

In the bottom of the first that night, Clemente bounced a ball up the middle that New York second baseman Ken Boswell got to, but the ball caromed off his glove.

Was it a hit? Well, you be the judge:

The scoreboard at Three Rivers quickly showed an "H" on the scoreboard, indicating it was his 3,000th hit. The operator jumped the gun. Luke Quay, the McKeesport Daily News editor, instead ruled it an error, since beat reporters would often rotate as official scorers as well. ("$50 a game. Couldn’t beat it," quipped Smizik.)

“They never should have put a hit on the scoreboard," Smizik said.

The operator changed the board to an E, drawing some confusion and boos. Postgame, Clemente was upset. It was far from the first time he had a hit taken away from him, usually a product of him being a Latino ballplayer in a league that had integrated less than a decade before he debuted in the majors.

“I truly believe he would have won maybe three more batting titles if it wasn’t for the blatant calls [against him] and how hard he had to work to get his hits," Clemente Jr. said. "Not have them taken away from him. They had to be clean.”

Clemente did soften his tone when he found out it was Quay, who he considered a friend, who made the ruling. Instead, he said he would just get it tomorrow.

“For me, I thought it was a hit, but dad really wanted that clean hit," Clemente Jr. said.

____________________

If he wanted a clean hit, he got in the fourth inning the next day. Clemente got a diving 2-2 Jon Matlack curveball away and drove it to left-center for the most famous double in franchise history.

“We had the angle from the first base dugout," Blass said. "We knew it was a gap shot the moment it left the bat. It was immediate. We didn’t have to wait for the ball to fall or get through an infield. It was a ringing double. We were on our feet immediately.”

“I felt so good that it was a ringing double," Blass added later. "It was not just a scratch base hit. It was his with authority, the way that a 3,000th hit, in my mind, should be.”

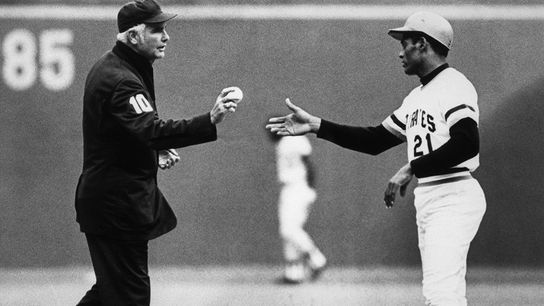

Clemente doffed his cap, second base umpire Doug Harvey handed him the ball Mets shortstop Jim Fregosi retrieved and Clemente would exit the game shortly after. The Morris Berman photo of Clemente at second would go down as one of the most iconic photos in Pirates history.

“I will have that image in my mind forever," Blass said. "I love the statue the way it is down by the bridge. However, if I had to choose, I would have chosen that stance at second base.”

When he returned to the dugout, Willie Mays, who had been traded to the Mets earlier that season, came over to hug him. The two future Hall of Famers weren't particularly close, but it was an embrace of what was at the time two of the 11 players who had reached that hit plateau.

“Just the mutual respect for professionalism was captured," Blass said. He would then quip, "If only Henry Aaron was there too.”

If there was one thing to spoil it, it was the attendance figure: 13,117.

“I wish there would have been more fans in the stands to see history," Oliver said.

There are several theories for why Three Rivers Stadium was mostly empty that day. The Steelers were becoming a hotter ticket, people were waiting to go for the playoffs rather than late-season regular season games that had no barring on the standings, Pitt football was playing that day. But as strange as it may seem considering all he did to that point, it may also be because Clemente was not as beloved then as he is now.

“Both of us believed in justice," Oliver said. "We believed in that. Back then, our wives were saying that our personalities were very similar. We believed in the same things.”

Oliver said he didn't know if those calls for justice were part of the reason why there weren't more people lined up for that game. David Maraniss, the author of the biography Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball's Last Hero, implied as much.

“A lot of it had to do with the social mores of that time and place,” Maraniss told the New York Times in 2011. “Pittsburgh was the quintessential white working-class steel town, and the Pirates were seen as ‘too black.’ Only the year before, they had fielded the first all-black and Latino team in major league history.

“After Clemente died, he was martyred in Pittsburgh and everyone said they loved him, but that was not the case when he was alive. He had to overcome a lot in terms of race and language in Pittsburgh, and did not really win the city over completely until he died.”

MORRIS BERMAN / GETTY

Roberto Clemente records his 3000th hit as Mets catcher Duffy Dyer prepares for a ball in the dirt.

____________________

Clemente Jr. was not among those in attendance in Pittsburgh that day. He was at home, just outside of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“Dad was very strict in terms of us being born in Puerto Rico, but also school," he explained.

When Roberto and his wife, Vera, were away, the Clemente boys would stay with a neighbor, the Lopez's, and their nanny, Maria. So from 1,700 miles away, they, like so many others, watched it on TV.

“Everyone in Puerto Rico was paying attention to every at-bat," Clemente Jr. said.

Watching it together, Clemente Jr., then 7, started bouncing off the walls when the ball landed in left-center.

“I knew it was a happy moment, but [I did] not really understand the magnitude of that moment until later on," he said.

That's partly because when his dad was home, the conversations weren't about baseball. It was about being a dad, making music, tending to the animals they had. It was just a hit to a 7-year-old son, but with 50 years of context, it's grown into more.

“The more I think about that moment of him standing on second base, to have that moment, that feeling of accomplishment, pride and understanding that he was representing all minorities at that moment," he said. "He carried that all the time, from day one to the last day. He was representing all of us, really.”

____________________

Those who picked up a copy of The Pittsburgh Press on Oct. 1 may have been puzzled with the layout choice that day.

“That’s one of the great newspaper stories of all-time," Smizik said.

Smizik's story about Clemente read "Clemente Gets 3,000th. Will Rest Till Playoffs." It was a sidebar to the allegedly big news story of the day: Pitt football just lost to another bottom-feeder program that year, Northwestern, to fall to 0-4, en route to a 1-10 season.

“The players didn’t like to acknowledge whatever you wrote," Smizik said. "But when I walked into the locker room the next day, they were screaming and yelling at me because of the absurdity of the situation.”

The culprit, Smizik suspects, was his editor, a Pitt graduate who perhaps let some personal feelings about their alma mater get in the way of what the city's sports fans would actually want to read.

“I think he expected that Pitt would be at the top of the page, and that’s what he did," Smizik theorized. "... The Sunday sports editor was one of the worst newspaper men I ever worked with. It could have been his doing, too."

____________________

MORRIS BERMAN / GETTY

Roberto Clemente is handed his 3,000th hit by second base umpire Doug Harvey.

That would be, of course, the last regular season hit of Clemente's career. He rested the remainder of the season for the playoffs, where the Pirates lost to the Reds on a wild pitch in game five of the National League Championship Series. Three months later, he took off on that fateful flight pointed towards Nicaragua.

He could have kept playing. Smizik said he was 38, but "looked and played like he was 28." His OPS that season was right in line with his career average, and even if his arm was not quite at its peak anymore, if a runner was on first base on a hit to right, Smizik said they still jogged to second because they didn't want to risk going to third.

“Only he knew what his standards were," Blass said. "We’ll never know. What a way to go out, landing right at 3,000. I was honored to be there watching that.”

“It is very mystical that the story ends with 3,000 on the dot," Clemente Jr. said. "I think because of that, he became the gatekeeper of the 3,000 club.”

Friday, he'll be celebrated as a ballplayer. On Saturday, efforts will continue on the Clemente family's part to help after Hurricane Fiona struck Puerto Rico, a fitting extension of his actions off the field.

"It's going to be a special day for us," Clemente Jr. said. "Not being in Pittsburgh will be pretty strange, but I think what we are doing [in his] memory is something that is always going to be a positive thing to what’s going on around us.”