Wil Crowe didn't know he was a slow worker until he became a Pirate. It wasn't an analyst or coach who told him, but rather, his teammates.

"Ben Gamel always gave me s--- last year," Crowe told me. "He would always say, 'you can work faster, if you want.' It's a joke, I get it, but I wore it last year."

Crowe definitely took his time between pitches last year. Whenever there was a runner on base, he averaged 27.2 seconds between pitches. According to Baseball Savant, that was the fourth-slowest time out of the 81 pitchers who threw at least 1,000 pitches. He led the team with 25 starts, and 20 of them took at least three hours to complete.

He's sped up his pace this year, shaving about two seconds off his normal pace when the bases are empty (18.8 seconds last season to 16.8 seconds) and nearly three seconds whenever there is a runner on base (27.2 seconds to 24.3 seconds). The quicker, more consistent pace has commonly been cited as one of the reasons why he took a step forward this season. Crowe says he is pitching with more confidence than he did as a rookie, which is why he has sped up.

There's a good chance that in a year or two he will pitch at an even quicker pace, perhaps not by his own choice. It could be dependent on the pitch clock coming to Major League Baseball.

For the first time in 2022, all minor-league games have operated under a pitch clock. If there is no one on base, pitchers have 14 seconds to start their delivery. If there is a runner on base, it's 18 seconds, and a pitcher only has two attempts to pick off a runner. If they try and fail a third time, the runner gets the base automatically. Hitters get one timeout during a plate appearance. If a pitcher doesn't deliver a pitch in time, they are called for a ball. If a hitter is the offender, it's a strike.

Ever since MLB took over minor-league operations after 2020, the minors have become the league's preferred way to experiment with potential new rules, such as automatic strike zones and banning infield shifts. The pitch clock is their most ambitious new rule since it was implemented at all levels of the minors, and it's perhaps the most important for the future viability of the sport.

That's because baseball has a problem that is potentially scaring away fans: Games are taking too long. Ever since 2014, the league has instituted pace of play initiatives to try to speed up games. Pitchers must face at least three batters, cutting down on the number of times a team will make multiple pitching changes in an inning. Pitchers no longer throw four pitches for intentional walks, and a batter can be sent to first instantaneously. Batters now must stay in batters boxes, and time between inning breaks is more uniform.

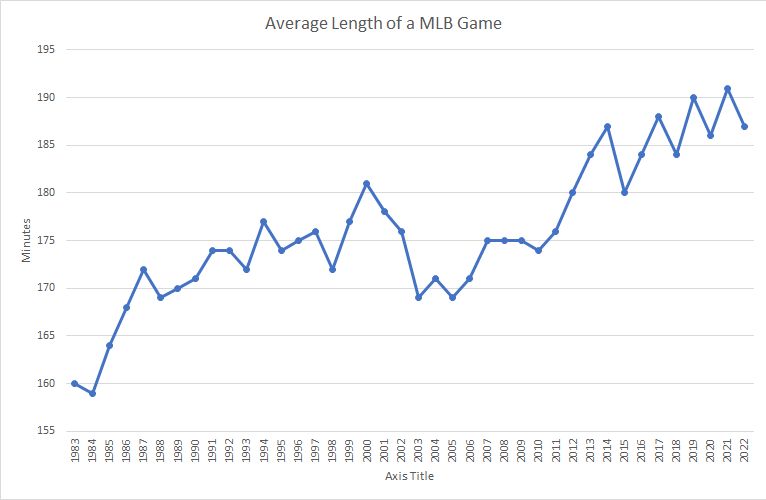

It hasn't amounted to much. After a long plateau just under the three hour mark from the 90s to 2011, games have averaged at least 180 minutes every year since 2012. Entering play Sunday, the average major-league game took three hours and seven minutes to play. If that stands, it will be tied for the fourth-longest game average in league history, just four minutes shorter than the 191 minute record average from a year ago.

Don't buy into that small dip in length too much. A game takes almost half an hour longer to play now than it did 40 years ago, and 15 minutes longer than 20 years ago:

DATA VIA BASEBALL-REFERENCE

This isn't necessarily the product of the league becoming more home run/walk/strikeout focused. In 2003, the year with the quickest games in the 21st century, there were 283 pitches thrown and 77.1 batters per game, on average. In 2011, the last year before the spike to the three hour average, there were 291.5 pitches and 76.3 at-bats per game. In 2022, there are 291.8 pitches and 75 batters per game. The numbers are trending towards fewer hitters coming to bat and slightly longer at-bats, but a nine pitch difference over 20 years doesn't explain why games are taking 15 minutes longer.

The league and players association previously discussed a pitch clock in 2018, but the league opted not to adopt it unilaterally after the MLBPA objected. As part of the new collective bargaining agreement the two sides reached in March, the owners could implement as soon as 2023.

Considering some teams, like the Pirates, have moved up start times from 7:05 p.m. to 6:35 p.m. to try to make sure guests can get home at a reasonable hour while games take longer, it seems like this could be the last year games are played without a timer.

Fans complain about game lengths, and players notice, too. During the past offseason, Quinn Priester was struck by how he could leave his Chicago home, attend a Bulls game and then be back home in about three hours.

“You can’t do that in a baseball game," he said. "It’s gonna be at least, 30-45 minutes to get there, you want to get there early. And then when the game starts, you have all the waiting around. Some pitchers take for-frickin’-ever. It’s annoying."

____________________

When Kieran Mattison and his coaching staff caught a major-league game earlier this year, one thought kept coming up in conversation.

"Man, they need the clock."

"We were timing how long it was taking guys to get in the box," the Class AA Altoona manager said. "It shouldn’t take that long.”

Forgive Mattison and his coaches if they're used to a faster-paced game. They've been playing them all year. In 2021, minor-league games also took over three hours to play on average. This year, it's just over two and a half hours, all while having no noticeable impact on the league's offensive performance.

Impact of the pitch clock in the minors pic.twitter.com/Q3V3OOAulf

— CJ Fogler AKA Perc70 #BlackLivesMatter (@cjzero) August 23, 2022

“It forces the game to have action," Mattison said. "When you watch football or a basketball game, it’s constant action. The timeouts are the timeouts, but most of the time, you’ve got action. I think the clocks have been beneficial for the game because it forces more action.”

"We’ve just taken away time where nothing’s happening,” Priester said.

Jonathan Johnston, the Class Low-A Bradenton Marauders manager, is also pro-clock. Not that he needed convincing, but last month, the Marauders found themselves in a rare 12-inning ball game. It took three hours and 42 minutes to complete the game, minus a rain delay. The Pirates have played five nine-inning games this year that took longer than that to complete. The majors cannot compare to how efficiently minor-league games are played.

“We will have big-league guys come down and rehab, and it’s awkward because we’re playing at a much faster pace," Johnston said. "It’s almost weird to slow down.”

There were some initial grumbles at the beginning of the year when the pitch clock was announced, but they were done within the first week, Mattison said. The same happened whenever he was a coach in the Arizona Fall League last year.

“Baseball players are the most adaptable people on earth," Mattison said. "You’re constantly moving to a different city. You may have a different teammate tomorrow. The game, you have to adapt. You have to adapt and you have to adjust. … When they get used to it and know it’s part of the game, they’ll adapt.”

And while the image of a Max Scherzer meltdown because he was penalized for a ball four because he didn't start his delivery in time is potentially hilarious, by Johnson's count, there are only about one or two penalized strike or ball calls during a weekly series anymore.

“If you struck out on a bad call, it’s the same thing," Johnston said. "Guys get emotional. It happens. It’s part of the passion of if. Once you realize how important it is, you start taking the steps necessary to make sure it doesn’t happen.”

“The clock ain’t the excuse of you getting out," Mattison said. "The clock ain’t the excuse of you not being ready.”

There is nothing quite comparable for the major-league game, but the fact that minor-league games are being completed in the time it took to play them 40 years ago offers a unique possibility for the sport. So many recent rule changes, like the National League adopting the designated hitter this year and banning shifts next year, have been made to try to make the game more engaging, but that can only go so far if the ball is still in the pitcher's hand.

“Quite honestly," Johnston said, "I want to see the game be played.”

____________________

Compared to the rest of the league, the Pirates play shorter games. Their three-hour, five-minute average is the quickest of all National League clubs, and the fifth-briskest in the sport.

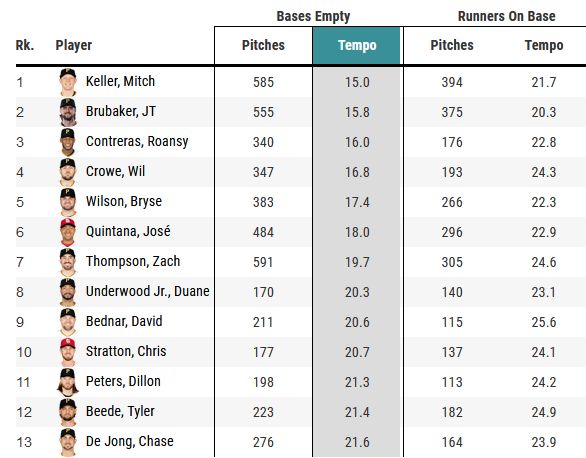

That doesn't mean they're well positioned for a jump to a minor-league paced pitch clock. In fairness, very few major-league pitchers are. Baseball Savant tracks the pitch tempos of 390 qualified big-leaguers, and of that group, just three average fewer than 14 seconds with the bases empty, and none of them have a pace lower than 18 seconds, both of which are the rates minor-leaguers are playing this year.

Of course those numbers are not set in stone and the league can adjust. But going by the tempos of Pirates' pitchers, many are going to have to speed up significantly.

DATA VIA BASEBALL SAVANT

A slow tempo isn't necessarily a bad thing now without the clock, and those who take longer aren't against the idea.

“I’ve heard good things from guys in AAA about it," Tyler Beede, who averages over 21 seconds between pitches, said. "I think if they incorporate the PitchCom [a device that allows catchers to relay what pitch to throw via a remote and a speaker in the pitcher's hat] with it, it would be easier in terms of stepping on the mound and knowing what you’re going to throw rather than then getting signs from the catcher."

The general consensus among the pitchers polled in the Pirates' clubhouse is that they're at least open to the idea if it could speed up games, something that is advantageous for both themselves and the sport. There are skeptics, though.

“I personally don’t think it’ll work in the big leagues, but I think it’s fine in the minor leagues," Austin Brice, a veteran reliever who has bounced between the majors and minors this year, said. "It keeps the games going, but it does completely eliminate some elements of the game that you just need at the big-league level, like holding runners. … It essentially eliminates that part of the game.”

For transparency sake, Brice said he has been penalized a "double-digits" amount of times this year for taking too long. But his point about the running game was the one consistent criticism about the pitch clock. Any disengagement from the rubber counts as a pickoff, and if a pitcher disengages three times without picking off the runner, then they get a free base.

So pitchers only get two pickoffs to try to get the runner. If we're being honest, it's only one, because failing a second time gives the base runner more leeway, knowing they can take the extra step because diving back to the bag counts just as much as a stolen base at that point. And when the clock starts to wind down, the pitcher may have to choose between taking an automatic ball or giving the runner a head start of knowing exactly when he will begin his motion home.

“Sometimes that time can run pretty quick, and those are the most stressful times too with guys on base," Priester said. "It creates a little more stress for the pitcher, I think, but again, it’s a good thing at this level. You want to be challenged every way you can. That’s where you find out what’s wrong and what you need to get better at.”

That's fine for a young pitcher trying to figure things out in his developmental journey to the majors. But when you're in the majors and have to perform every time you get the ball? It can be scary.

"I think with nobody on, pitch clock’s great," Bryse Wilson, another pitcher who has split time between the majors and minors, said. "I think it could be really helpful to the game and the pace of the game, but I think they have to reassess the rules that come with it as far as pickoffs, step offs, stuff like that. It makes holding runners a whole lot harder than it already is.”

Johnston's suggestion is the pickoff rule should be reset once the batter takes the base, rather than the current rule where disengagements are tracked by the hitter at bat. But adjusting other rules to accommodate a pitch clock opens up a new can of worms.

“For something like that to work in the big leagues, I think you have to limit base running, and I think that’s just a snowball effect for completely diluting the game,” Brice said.

“[Minor-league] games aren’t necessarily played to win championships," he said shortly after. "Games are played for development and to help the big-league team out. I think when you’re playing at a championship level like Major League Baseball, you can’t dilute the game like that.”

____________________

Brice is skeptical. Some skepticism is good. Shorter games are also good.

“I don’t know how much shorter games are going to be," Crowe said. "I think the hour 50 [minute] games happening in the minor leagues are a little egregious, but the 3:30, 4 hour games will probably fiddle their way out.”

Nobody, including the league and the MLBPA, are looking for a radical change of how the game is played with the clock, but the minors does offer some optimism of a real way to combat longer game times after a decade of negligible results. It will also be the most drastic change, and one that there will surely be some opposition to among the major leaguers.

“It’ll be like any change," Johnston said. "It’ll hurt initially, guys will complain, this and that and they’ll adapt because they’re competitors, and they’re going to do whatever they have to to win.”

We will very likely see if Johnson is right sooner rather than later.