The Penguins aren't strangers to injuries plaguing their lineup nearly every season. The injury issues go all the way back to the days of Mario Lemieux.

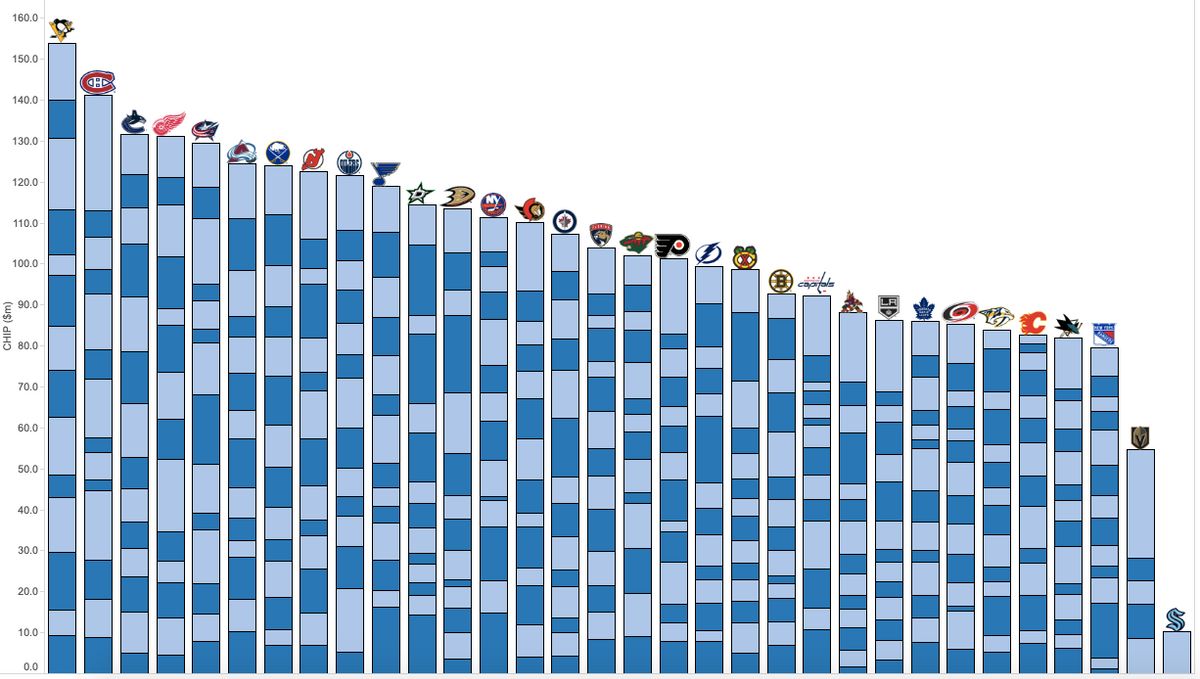

There isn't a single NHL team that has lost more salary cap value to injuries than the Penguins since 2006-07, according to NHL Injury Viz. Over the past three seasons, the Canadiens are the only team that tops the Penguins in that regard.

NHL Injury Viz

CHIP = Cap Hit of Injured Players (2006-2022)

Are the injury problems over the past several years due to the system Mike Sullivan employs? Personnel? Bad luck?

Well, it's complicated.

I consulted former Toronto Marlies assistant coach and author of "Hockey Tactics 2022: The Playbook", Jack Han, for further insight.

"The number one way that coaching would cause players to get injured more often than they should, is overtraining," Han told me Wednesday afternoon. "Whether it’s training too often, whether it’s doing too many sprints, whether it’s having too many full-contact practice drills. I think there's way more things that teams can do incorrectly in practice versus in games, because in games, I think systems are pretty homogenized. There's not really a specific system that would cause players to get injured more, but how you train definitely could have a very big impact."

Han then explained a study that was done by a National Soccer Federation in the 1990s to uncover why their players were slow, at least relatively speaking. It was discovered that the overall slowness had little to do with the individual players, or even the team's tactics. It had far more to do with the fact that they overtrained when they were young. The players that were naturally fast ended up getting injured frequently because they were asked to work too hard. Injuries add up over time and eventually make you slower.

Now, Sullivan wasn't responsible for the training his players endured during their developmental years. That's obvious. But what about the training he is in control of?

When Han worked in the Maple Leafs' organization, their sports science department was proud of the fact that the entire team went several years without a single groin injury. Groin injuries in hockey typically occur from putting the body under too much stress for too long. That meant their load management programs were largely effective.

"Basically, we practiced less, we practiced with good intensity and good purpose, but we didn't mindlessly skate players," Han said when explaining their load management program. "That was one thing that we did to minimize the sort of soft tissue injuries. Obviously, hockey is a very fast sport and a very physical sport. So you can't prevent all of these injuries. But certainly, with a load management program, you can prevent some."

Sullivan has mentioned load management numerous times throughout his tenure with the Penguins. He also frequently refers to the knowledge of his medical staff and has explicitly said their input is invaluable to him. That's not a coach that is overtraining his players. He's demanding, no doubt, but overtraining? That doesn't hold much weight here.

Even as recently as the Penguins' first-round Stanley Cup playoff matchup with the Rangers, Sullivan required his skaters to hit the ice just once in between games. That's rather common around the NHL, but again, this is a coach that is more than cognizant of his players' workloads. Some players that were clearly banged up during the series weren't required to skate at all in between games.

From there, our conversation shifted toward individual players and how a history of injuries makes them that much more susceptible to re-injuring themselves.

"Maybe the first time you get injured, it's an accident, but then after a certain point, it becomes something that flares up and something that is vulnerable. So why are the Penguins so often injured? Maybe it's because they have a lot of players who are carrying chronic injuries."

My mind immediately jumped to Jason Zucker. After missing two and a half months due to core muscle surgery, Zucker returned, only to get injured in his first game back. He didn't return to the lineup for nine days. Through the end of the season, Zucker was clearly playing with a hitch in his giddyup, and even sat on a stool when he wasn't on the ice rather than the Penguins' bench.

At Zucker's end-of-season media availability, he said surgery, while not imminent, was on the table this offseason.

"If he's trying to play through all these major injuries, then obviously not only is it going to affect his performance, but it's going to set him up for related injuries," Han said when I brought up Zucker. "In other cases, the players maybe hide their injuries and push themselves to come back sooner. But certainly, I think that is the biggest piece when it comes to certain teams seemingly getting injured all the time."

Aside from Zucker, Sidney Crosby missed 13 games this past season, most of which were due to offseason wrist surgery that probably should have been done years ago. Bryan Rust missed 20 games with various injuries. He has missed stretches of games every season of his career. Evgeni Malkin missed half the season before returning from knee surgery. I don't need to tell you about his injury history.

"Their good players are a little bit older. Their complementary players are a little bit smaller. Some of their players are carrying chronic injuries. That’s a perfect storm for having a lot of injuries because of the way that you play and all those different factors coming together."

That brought us to our next talking point, where Han said the Penguins being an undersized team in general is inherently going to play a part in their frequent injuries, along with them preferring to play a straight-ahead game and hang on to pucks to make plays rather than throwing them away.

"If you look at the Penguins, it's a smaller team, just vertically speaking. They look to play with skill, they look to make puck plays, but a lot of times, it's that incidental contact that ends up head level," he said. "If you're looking to play fast and advance the puck, then the player who's receiving the puck has to be elite at shoulder checking and identifying pressure and putting himself in a position where he can protect himself. In the heat of battle, you don't always have the time to do that. And if you’re coached to take a hit to make a play, which Pittsburgh does, then that's what happens sometimes."

Don't let that fool you into thinking Sullivan needs to overhaul his system to the point where players are wasting pucks and opportunities at the first sign of pressure, though.

"But then again, I don't think any any NHL coach would tell their players to bail out on these plays. So I don't think it's a Penguins specific problem. It's just the nature of the game at this level. The Penguins play on the edge in terms of maintaining possession, or in terms of being aggressive on the forecheck or in terms of initiating contact and taking hits to make plays."

Han added that while the Penguins are a bit progressive in their tactical approach, they don't stray too much from the foundational tactics that are commonplace around the league.

The question had to be asked: Can the Penguins mitigate this problem -- even slightly -- by adding more size to the team?

I've never been a proponent of adding size for the sake of it. That said, the Penguins are susceptible to getting physically outmatched on occasion and, in theory, could kill two birds with one stone by adding some size.

Not so fast.

"The problem with getting heftier guys is that the bigger and heavier you are, the more vulnerable you are to certain types of injury, like soft tissue injuries or overuse injuries or just not being able to get out of the way of an impact," Han said.

Brian Dumoulin ring a bell? He had several significant lower-body injuries starting with the 2019-20 season, and even though he didn't miss many games this past season, had the worst year of his career. It ended by tearing his MCL in Game 1 against the Rangers.

The grass isn't always greener. In reality, injuries are going to happen no matter what. That's just the nature of the sport.

Still, there's got to be something the Penguins could do to minimize injuries.

As it turns out, Han believes the Penguins could alleviate this issue by injecting something they haven't had much of in recent seasons.

"The solution to the Penguins’ injury troubles, it's not more size necessarily, it's more young players being incorporated into the team."

He compared it to driving an old car, another simple, yet resonating analogy that flows out of him with regularity.

"Older cars are going to break down more. At some point, the only solution is to replace it with a new car. If you're not able to replace this team with younger pieces gradually, then you're only going to experience this problem more and more throughout the years."

Players like Rust, Jake Guentzel and Conor Sheary complemented the Penguins' group of veterans in 2016 and 2017 when they won back-to-back Stanley Cups. Since, the Penguins haven't had any young talent that even sniffed the levels of any of the three players mentioned.

It's an effect of trading draft picks and prospects year after year to remain competitive.

Due to the Penguins' salary cap constraints, they might be forced into giving lineup spots to younger players such as Drew O'Connor, Valtteri Puustinen and Sam Poulin next season. At 26, he might not be as young, but with minimal wear on his tires, Radim Zohorna is intriguing as well.

Father Time comes for all. The Penguins aren't an exception. And really, it's impressive that they've even stayed competitive for this long despite the long list of injuries to their stars over the years, let alone further down the lineup.