CHICAGO -- The early stages of the regular season are often the most experimental. Perhaps a pitcher made a mechanical change during the offseason and they finally get to make some changes. Maybe they have some new velocity, or a new game plan of how they want to attack hitters.

Not all of these tweaks will work, but that’s what makes them exciting. The first month and change is the wild west. Maybe that new idea was just what a pitcher needed to break out. Maybe it was a terrible idea and you need to revert back. Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

And if you’re a Pirate pitcher, they need to be looking for gains. We’ve seen changes with how they deploy their bullpen and how it’s clicked for a couple pitchers. I’ve chronicled a couple of other changes that have done wonders for pitchers already this season, like José Quintana relying on his offspeed stuff more and Wil Crowe and Dillon Peters becoming two of the better relievers in baseball.

Let’s do a couple more. Here are three pitchers who have made adjustments this year that are worth a deeper dive.

THOMPSON STRAIGHTENS OUT

After a shaky first month of the season, Zach Thompson has been terrific in May, going 12 scoreless frames without allowing an extra-base hit. He’s back to throwing the cutter more, which was his best pitch with the Marlins last year and a plus offering in general, and his four-seamer is getting a whiff one-third of the time batters swing at it. Walks have done him in a couple times this year and the team’s experiment to boost his sinker from his fourth offering to his primary non-cut fastball hasn’t gone smoothly thus far, but there are some encouraging signs here.

The most encouraging development isn’t going to show up on the back of a baseball card. He’s no longer drifting during his delivery.

The part of the body that needs to be watched the most, according to Thompson, is his head. If he tilts it during his delivery towards first base, his whole body is going to go with him. If he keeps it straight, his mechanics are cleaner.

Talking to Thompson this week, he said his relief outing in Detroit was the most exaggerated example of his head movement. Let’s compare that to his most recent start Saturday:

Look at how Thompson finishes. In his outing on May 4, Thompson goes a lot more horizontal and his whole body continues moving, to the point that his right arm touches his left hip and he takes a sizable step to first base. On May 14, in addition to the whole motion just looking a bit shorter and quicker, Thompson stays more upright and his step to first is a lot smaller. More of the energy his motion creates is going towards home plate. Not only does that mean a little more perceived velocity, it means he won’t cut all of his pitches. Thompson has a good cutter, but that doesn’t mean he wants all of his pitches to cut. That leads to missed targets and mistake pitches.

Thompson is a big guy, standing at 6’7”, so there’s a lot of body movement there to keep track of. If he keeps his head straight, he should be able to stay on the right pitch path.

KELLER’S DISAPPEARING BREAKING BALL

I wrote about Mitch Keller’s fastball earlier this week and how despite getting that coveted extra velocity, it is still getting hit.

But there was something else worth noting about that start Friday. Keller threw 80 pitches, but only three of them were curveballs.

Coming up through the minors, Keller’s curveball was considered a plus pitch. It still moves a ton, averaging 59.3 inches of vertical movement (6.6 inches more than the average curve) and 11 inches of run (three inches more than average).

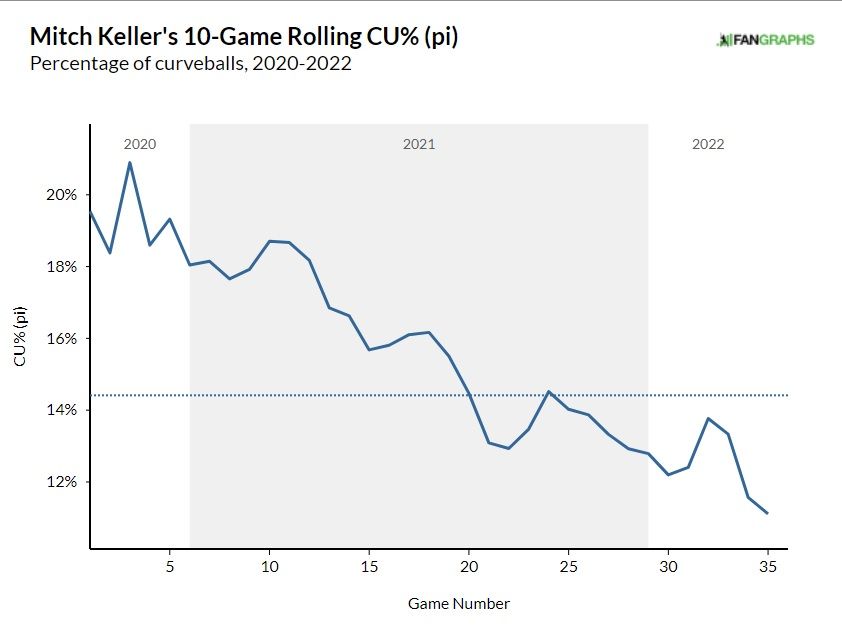

Despite that, he’s throwing it less and less. This isn’t a 2022 development, either. It’s been continually thrown less and less since his sophomore season:

Something similar happened to Jameson Taillon in his time with the Pirates. He came up through the system as a fastball/curveball/changeup guy and then found a slider. He threw the slider more and more, and the curve was a pitch that was used less. The two pitchers were in the majors under different regimes and pitching coaches, but I couldn’t ignore this. It happening twice is coincidental. If we see it again, I’ll call it a trend.

There is an elephant in the room that needs addressed here: Keller’s curve got hit hard last year. Batters had a .452 batting average against it, and the peripherals didn’t paint much prettier of a picture. That batting average against curves has been cut in half to .214 so far this year, but it is a small sample size and the batted ball metrics for it still aren’t that great.

But looking at the batted ball metrics is kind of missing the point with Keller. What he needs right now, more than anything is whiffs. The fastball isn’t doing it, and this is the third year where his whiff rate has leveled out and about six percentage points lower from when he was a rookie:

-original.jpg)

The curve only has a 20% whiff rate so far, so basically what his other three pitches average. It would need to be a leap of faith that the shape can change the eyeline and get whiffs by tunneling off the fastball. Part of the reason for that extra velocity was to make the breaking stuff play better. If the fastball is being hit, maybe the breaking balls should be emphasized more.

SOME EXTRA HEAT FROM AN UNEXPECTED SOURCE

Ok, did you read that third section of this article? About how velocity isn’t everything? You did? Ok, good.

Duane Underwood Jr. is bringing heat. Unprecedented heat for him, even:

-original.jpg)

Underwood has averaged 96.4 mph and 95.9 mph on his fastball in his two outings so far this year. His previous career best for an outing was 95.9 mph. He’s in the 83rd percentile in fastball velocity this year, a big jump from last season when he was just a little better than average.

Back in spring training, Underwood talked about how he went to a specialist to help him with his hips this winter and it’s helping him open up more during his delivery. He had been dealing with nagging hip issues for awhile, and this spring was the best it felt in a long time.

An opening day hamstring injury has limited him to two outings, and three earned runs in two innings pitched isn’t exactly a great way to get out of the gate. But last year, Underwood had pretty good results with the changeup and curveball. If he’s improved the heater, then this could be the start of something.

Underwood is also in a unique spot in the bullpen. He’s a potential hybrid pitcher, the second guy who comes out and throws two or three innings, like Crowe or Peters. They have been terrific this season, but they don’t throw hard. In fact, the only hybrid candidate that we’ve seen so far who really can throw hard is Max Kranick, who is in Class AAA Indianapolis. If the goal of that type of pitcher is to challenge hitters with a different look, imagine seeing 90 mph in your first at-bat and then 97 mph your second. That can mess with their timing all game.

Last year, Underwood proved to be, at the very least, an inning eater. If he can find a way to bump up his whiffs and strikeouts to even league average amounts, then this type of role could fit for him. His secondary stuff played well last year, but it sometimes forced him to nibble. Being able to attack with an upper-90s fastball could make nibbling less essential.