COLUMBUS, Ohio -- It was obvious the Penguins' penalty-kill would miss Teddy Blueger while he recovered from a broken jaw, but the extent to which they've struggled has made it crystal clear that he sets the tone for the entire unit on a nightly basis.

The Penguins still boast the NHL's second-best penalty-kill at an 86.5% success rate, but in the 11 games since Blueger's injury, they have managed to kill only 76% of the opposition's man-advantages.

Beyond their raw penalty-kill percentage, the Penguins were ceding an incredible 3.93 goals per hour while short-handed in 41 games leading up to the injury. That rate went down nearly an entire goal per hour to 2.96 when Blueger was one of the penalty-killers on the ice. It's almost unfathomable, but that figure skyrocketed to a pace of 9.91 goals against per hour upon his exit from the lineup.

With the exception of Evan Rodrigues, who has seen fewer than four minutes on the penalty-kill with Blueger out, the Penguins have been trotting out their usual forward personnel that includes Jeff Carter, Brock McGinn, Zach Aston-Reese and Brian Boyle, so how could their results be so drastically different?

On Wednesday, Mike Sullivan told reporters in Cranberry, including our own Dave Molinari, that the penalty-kill has gotten away from a few key ingredients.

"Things like winning faceoffs, getting 200-foot clears, limiting zone entries," Sullivan said.

Surprise, surprise, Blueger has prospered in all three categories this season.

The rest of the Penguins' penalty-killers have shown the ability to prosper in those areas, as well, but their lack of attention to detail and inability to execute in critical moments has been a lethal one-two combo, along with Blueger's injury.

Let's dig into Sullivan's list.

LIMITING ZONE ENTRIES

When you think of defending the blue line, you have thoughts of defenders maintaining strong gaps and swatting the puck away, or backcheckers swooping in from behind the play to interrupt the puck-carrier. But more often than not, those plays are able to develop because of the things that happened at the other end of the ice just moments before.

It's certainly easy (and definitely not wrong) to credit a defenseman for sealing the attacker off along the boards after stepping up at the perfect time. But how about the forechecker who took away the middle of the ice and forced the opposition to the outside and right into the trap?

On the penalty-kill, as well as five-on-five, the Penguins do an incredible job of angling their opponents into suboptimal areas of the ice. It's a huge part of their identity and a major factor as to why they can be so hard to play against.

That said, it's an extremely demanding part of the game, both physically and mentally. When the attention to detail isn't there, the opposition will pick you apart:

The term "flush" is when a forechecker skates behind the net in pursuit of the puck-carrier to force them out the other side, typically into more forechecking pressure.

On the penalty-kill, however, a poorly executed flush will often result in the opposition getting the puck up ice with ease, displayed by Aston-Reese's poor route in Toronto last week.

Aston-Reese is cerebral with his routes more often than not, but in this instance, he failed to recognize that Morgan Rielly was almost as close to the corner as he was to being directly behind the net. Rielly's skates did indicate that he would skate the puck forward behind his net, so I can understand Aston-Reese's thinking that he could either make a play on him there, or force him to retreat out the other side. But Rielly's quick feet and awareness allowed him to escape pressure rather easily and, suddenly, Aston-Reese found himself above the puck at the wrong end of the ice while the Maple Leafs moved ahead five-on-three.

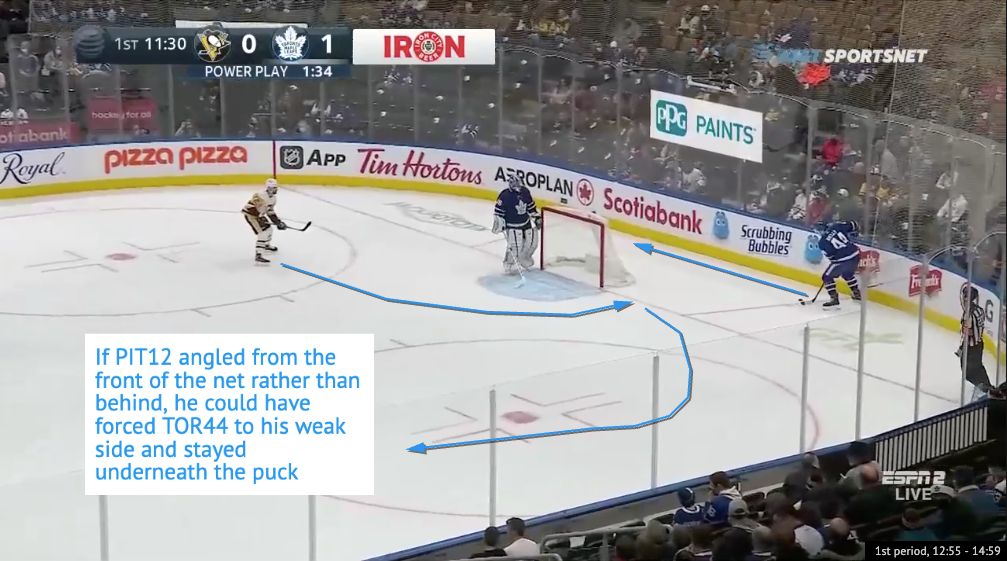

The Maple Leafs gained the zone quickly and got into their power-play formation, but had Aston-Reese taken an outside angle rather than going behind the net, the Penguins would have had a much better chance at disrupting the Maple Leafs' transition:

Taking the angle in front of the net most likely wouldn't have allowed for Aston-Reese to make a play on Rielly, but it would have forced him out the opposite side of the net putting him on his off-side, while Aston-Reese would be able to curl back with his momentum and stay below the puck. He would have had the option to continue his pursuit of Rielly, or fall back to the neutral zone and assume Boyle's role while he stepped up.

Aston-Reese had another rough go with Rielly the following period. This time, the mistake ended up in the back of the net:

Aston-Reese took his eyes off his assignment and disengaged for a split-second, but it was all the time Rielly needed to zip by him as Aston-Reese wasn't able to do much by way of forcing him to the outside.

By that point, Rielly was chugging full-steam ahead toward Boyle, who got caught in no-man's land. As soon as Boyle crossed his feet over to shift lanes, Rielly immediately cut in the direction Boyle just came from and blew around him, as well.

The Penguins' defensemen were nowhere to be found, as John Marino overplayed a potential pass to his assignment, and Brian Dumoulin got spun around to the outside and couldn't recover.

It was a phenomenal play by Rielly, but equally egregious on the Penguins' end.

GETTING 200-FOOT CLEARS

There's nothing overly technical or complicated when it comes to clearing the puck on the penalty-kill. Find a lane and send it hard toward the other end. Force the power play to spend time and energy retrieving the puck and getting set up again.

Of course, there is a level of awareness and anticipation necessary to be able to find those clearing lanes. The absence of that awareness and anticipation is a recipe for getting hemmed into your zone:

Against the Senators, Boyle supported the play down low as the puck bobbled around among skates and sticks. He hawked the puck, waiting for it to pop out in front of him so he could swipe it the distance of the ice. The puck did find him, but his clearing attempt ended up right on Thomas Chabot's stick at the point, and the Senators maintained pressure.

Boyle did not look up ice once after going below the goal line. Not a single shoulder check. If he had taken a peek or two, he would've noticed Chabot shading over to hold the blue line. Does that guarantee he would've gotten the puck out? No, but he never even gave himself a chance to identify an opening. Penalty-kills won't survive on hope and prayer-esque clearing attempts.

"Sometimes great players make great plays, and when you give them lots of opportunity with zone time, it puts a heavy burden and responsibility on the killers," Sullivan said.

Patrice Bergeron, Taylor Hall and David Pastrnak teamed-up to make the Penguins pay for Marino's weak backhand clearing attempt a few weeks back:

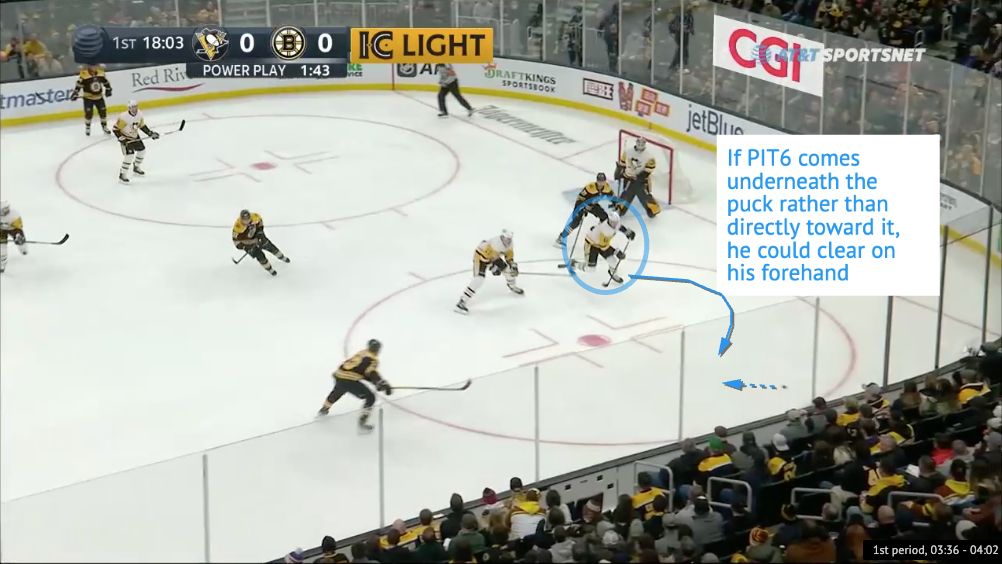

At a glance, it might seem like Marino did everything right except put enough mustard on the clear. But just as awareness and anticipation are vital to getting the puck out, so is positioning yourself to receive the puck in an optimal spot.

Notice how Marino took a straight-line route to the puck. Sure, he was the first one there, but he also put himself in a compromised position where his only option was to flail a backhander off the boards and hope it would squeak out of the zone. With Bergeron out there surveying the ice? Good luck.

If Marino had swung underneath the puck and taken a wider angle in his pursuit, he could have received the puck on his forehand and put enough strength behind his clearing attempt:

The argument could be made that swinging underneath would have caused Marino to be a split-second later to the puck, and thus, putting him under more pressure from the forecheck, but the play he made ended up in the back of his net. I'd take my chances trying to get the puck to the forehand.

WINNING FACEOFFS

I won't waste your time with clips of the Penguins losing draws that directly resulted in extended zone-time for the opposition, but I will tell you how downright atrocious their centers have been at the dot without Blueger, who has won 51.2% of his short-handed faceoffs this season.

Carter, who ranks 11th among all NHL centers in all-situations faceoff win percentage (56.6%), has won 45.5% of his short-handed draws since Blueger's injury.

Boyle's 45.6% faceoff win percentage in all-situations doesn't look so bad after uncovering his 30.8% win-rate at the dot in short-handed situations in Blueger's absence.

I'm not one to hyper-focus on faceoffs, but it goes without saying that short-handed draws in the defensive zone carry quite a bit more weight than even-strength faceoffs in the neutral zone.

This isn't something that I have tips on how to fix, and quite frankly it should level out over a larger sample, but that doesn't make things any easier to swallow in the present.

Even with Blueger, the Penguins' penalty-kill wouldn't have been able to sustain their staunch results for the entirety of the season. There was always going to be a correction. That said, this isn't a correction. This is the Penguins' penalty-killers letting subtle bad habits creep into their game. But with Sullivan and Mike Vellucci, who oversees the penalty-killing, both well aware of the issues at hand, there's no reason to believe the penalty-kill can't find a happy medium between its current state and what they showed earlier this season.