They are the most coveted coaching jobs in the sport.

There are only 32, spread among the NHL franchises that span the continent. Get one, and you're all but guaranteed of earning a seven-figure salary. Of possessing a high public profile, even if it's only in one market.

And, more often than not, of having the shelf life of a ripe banana.

Why NHL teams tend to replace coaches faster than clubs in other sports is open to debate, but few people in the business seem interested in disputing the basic premise that hockey turns over coaches more quickly than other pro leagues.

"You see times where coaches get moved out in hockey and I wonder why, at times, based on the jobs that they've done," Jim Rutherford said.

Mark Recchi agrees.

"There's not as much forgiveness and a little bit more, 'OK, well on to the next guy,' " he said. "I don't know if it's right."

There are, of course, exceptions. Lindy Ruff coached in Buffalo for 15 seasons. Barry Trotz matched that behind the bench in Nashville. Joel Quenneville spent 11 in Chicago.

Mike Sullivan, who has coached the Penguins since Dec. 12, 2015, hasn't matched those runs, but no one can say with any conviction that he won't.

Nearly six years after he replaced Mike Johnston, Sullivan is still getting through to his players, maintaining strong ties to his key veterans while coaxing maximum productivity out of players with more limited abilities and roles. Two of the Stanley Cup banners hanging in PPG Paints Arena testify to the impact -- and success -- that he's had. So is his distinction as the winningest coach in franchise history. He recorded victory No. 253 last Saturday, and there's every reason to believe that total will swell considerably before he leaves the position, because he still commands as much attention -- and probably a lot more respect -- from the players as he did on his first day as coach.

Sullivan readily acknowledges that he has evolved as a coach during his time here -- "He's done a good job of adapting," Sidney Crosby said -- and makes it clear that he believes it's important to do so.

"All of us in this profession, we learn from the experiences that we go through," he said. "When you're coaching the same group of players over the amount of time that I've been here and you build relationships with these guys, I think that warrants evolution in your approach."

But those who have worked with him say that all he has accomplished with the Penguins has not fundamentally changed the person he is,

"Sully has stayed true to himself," said Wild GM Bill Guerin, formerly of the Penguins' front office. "With all the success that he's had, especially early on, he stayed humble. He stayed on-point. He hasn't lost the trust of the group."

While that's just one of many factors that contributed to Sullivan's achievements here, Recchi -- a New Jersey assistant coach who spent three seasons on Sullivan's staff -- distilled the essence of Sullivan's formula for consistent success to a few words. Never mind that Sullivan works in a league where coaches routinely hit their expiration date after only a few winters.

"He just gets it," Recchi said.

____________________

GETTY

Mark Recchi, Mike Sullivan behind the Penguins' bench.

Sullivan seems to connect with his players better than any Penguins coach since Bob Johnson, and that's as much of a coincidence as it is when a Crosby shot from behind the goal line just happens to hit the back of the goaltender's leg and drop into the net.

Which is to say, not even a little.

If Sullivan were inclined to lay out the core principles of his coaching -- "I've never really given it a whole lot of thought, on how to articulate it," he said -- good communication surely would be one of the pillars on which his career has been built.

And that's particularly true in his dealings with the guys who play for him.

"He has a lot of respect from the players, that he earns," said Rutherford, the GM who brought Sullivan into the organization in 2015. "His communication and his willingness to sit with players, talk to players ... one of the things that really stood out with me was when he was dealing with some situations that were a little bit tougher with certain players.

"Everybody takes strong positions on their side (in such discussions). The player is going to feel strongly about how he feels, and the coach is, also. The thing that really stood out with me when I was in some meetings with Sully and a player is, they would talk through it -- he would let the player talk for as long as he wanted, say whatever he wanted -- then he'd say, 'I don't change my opinion, but what I'll do is, I'll meet you halfway on this. You meet me halfway, I'll meet you halfway.'

"There was that give-and-take, that the player understood that he was heard and they were going to try to compromise a little bit. I've heard him do that a number of times. It really works. And when you think about it, it's really fair. The player doesn't walk out of a meeting and say, 'Well, that was a waste of time.' He got to make his point and, hopefully, there's going to be a little give-and-take. And, as I always said, there was give-and-take."

Those conversations, Rutherford said, covered everything from players unhappy with their ice time to those displeased with the forward line or defense pairing on which they were being deployed. From why a player wasn't being used on the power play or penalty-kill to why he couldn't get into the lineup at all.

"All those things that a coach deals with," Rutherford said.

Sullivan said he tries to deal with them all in the same way -- directly and honestly, even if the player with whom he is speaking doesn't necessarily like the message being delivered. That is a vestige of Sullivan's playing days; he was a blue-collar forward in the NHL for 11 seasons, and knows what it's like to be sitting in the other chair during a player-coach discussion.

"I always appreciated coaches who communicated with me, defined expectations and provided feedback, with respect to those expectations," he said. "That's something I've tried to incorporate in my own coaching style. I don't ever like players to be guessing. I'm not a believer in mind games with players.

"I think players want honesty, and sometimes those conversations are difficult, but as long as they're done respectfully, I think players want that. I think players deserve that. They deserve honest feedback. They deserve clear expectations, so that they have an understanding of what they need to do in order to be successful.

"It's hard to win in this league, and I think that if I'm coaching my guys the right way, sometimes you're going to tell them things they don't want to hear. Those conversations aren't easy. They're difficult. It's not unlike being a parent. ... You're telling someone something they don't want to hear. But my feeling is, as long as it's honest and it's respectful, I think it will resonate with players. And when you work through those types of situations with players, over the course of time, your relationship with each individual becomes stronger."

Members of the Penguins' veteran core -- that would be Evgeni Malkin, Kris Letang and Crosby -- don't often have much reason to gripe, but Sullivan's interactions with them reflect the strength and significance of their relationships..

"The relationship he has with his leadership group is obviously tremendous, and he's built that right from the get-go," Recchi said. "That's a huge part of it. There's a great mutual respect between the leadership (and Sullivan). They have tremendous respect for each other. They understand what they've been through. They understand what they have to go through. They have that relationship, and it filters down to the other guys."

Those sessions, Crosby said, do not follow a schedule, but are held when circumstances call for it.

"We could meet once or twice in a week, and then go for a month or two months without meeting," he said. "It just depends on what's going on. But there's a level of communication where we know what's expected of us, as a group, or as individuals. ... He doesn't necessarily have to agree with some of our feedback sometimes, but I think he's definitely open to it, which I think is important and probably gives him a better feel for understanding us, as players.

"There's definitely a comfort level with the older guys, as far as they know what's expected of them. I think they feel comfortable sharing their opinion when he wants it."

Sullivan's close connection to his core veterans should not be construed as evidence that they dictate how the team is run. Crosby is not designating who gets a spot on the No. 1 power play. Letang does not construct the defense pairings. For while Sullivan isn't afraid to get input from them, he makes the final call.

"He's the decision-maker, but he listens, and that's really important," Guerin said. "Players, especially today, need to have some voice. This is not 1991 or before, where it's 'My way or the highway.' You have players with long-term contracts who make a lot of money that we need to work with. You have to give them a voice. They don't get the final decision, but you need to know how they feel.

"In the end, that's all they want. Players don't want to run things, as much as they think they do at times. Or think that would be the way to do it. Players are happiest when they're given an assignment, a directive. 'What do we need to win the game? OK, this is how we do it. OK, great. We'll do it.' But if players have a voice in that, it's even better."

____________________

DKPS

Sometimes, Mike Sullivan communicates at high volume.

Sullivan's current job is not his first running an NHL bench, and it's not the one for which he was hired before the 2015-16 season.

He was head coach of the Bruins in 2003-04 and 2005-06 -- the 2004-05 season was wiped out by a labor dispute -- and compiled a 70-56-23 record (with 15 ties). Boston won the Northeast Division in his first season, but was fifth in his second (and final) one.

Whether he was a culprit or scapegoat for the team's decline in the year following the lockout can be debated, but supporters are adamant that it is the latter.

"I admired him as a coach from a real early age," Brian Burke said. "Part of our job (as front-office executives) is to study coaches and get to know them as best we can and evaluate them. I think he's been coaching at a high level since he came in."

Rutherford was GM in Carolina when Sullivan was coaching the Bruins, but said they never had contact until Sullivan's tenure in Boston effectively was over.

"I was on my way to (the 2006) draft and he was sitting on the plane by himself," Rutherford said. "Because we were in the same league, we knew who each other were, but we hadn't met. He was kind of waiting to see what was going to happen with the Bruins, but it was leaning toward them not bringing him back. I just said to him, 'Hang in there, Sully. I think you did a great job and I hope you continue on with the Bruins.' Which he didn't."

In 2007, Sullivan signed on with Tampa Bay as an assistant to John Tortorella. It was the beginning of an apprenticeship that helped to mold Sullivan into the coach he had become when he joined the Penguins.

"He was under Torts for a number of years," Recchi said. "And learned a ton."

Although Tortorella can be a polarizing figure -- he can come across as prickly, to put it gently, at times -- his coaching acumen is widely respected in hockey circles.

"Working as an assistant with John Tortorella is always time well-spent," Burke said. "When you spend time as an assistant coach with a top head coach, that's not wasted time. That's well-invested time, and I think it's helped (Sullivan) to be a better coach.

"(Tortorella) has a reputation of being a hothead, but he's not, at all. He'll get mad, but he's a teaching coach. That's why he's had such success. With today's player, hollering at them doesn't produce results. You have to explain what went wrong, and how we fix it. Those are teams that excel and survive. The ones that teach and motivate, not holler."

The willingness -- and ability -- to instruct players on a daily basis is another key element in all that Sullivan has achieved here, and it's not as common in his line of work as some might expect.

"There are some guys out there who put a system into place," Guerin said. "And then, that's (the extent of) their coaching."

On-ice instruction is a regular feature of Sullivan's practices, something he and his assistants -- regardless of who they happen to be in a given season -- emphasize.

"Unless you're teaching as you go, you tend to have a short leash," Burke said. "The style of coaching you have directly impacts your ability to continue as a coach. And in Sully's case, he's a teaching coach. He's a motivational guy, but he's a teaching coach. That means you have a better chance of relating to the players over a long term."

After splitting from Tortorella in 2014, Sullivan spent a season in Chicago's player-development department. A year later, he turned up on the Penguins' radar when they were searching for someone to succeed John Hynes as coach of their farm team in Wilkes-Barre.

"Jason Botterill started doing a search for a coach in Wilkes-Barre, and he got it narrowed down to three guys," Rutherford said. "I said that having a guy with NHL experience -- the experience that Mike Sullivan had -- would make a lot of sense for us. His preparation, his focus, I'd be surprised if there's a coach who is better prepared than he is. The opportunity came where we were under-performing in Pittsburgh and they were over-performing in Wilkes-Barre; I think they'd won 12 in a row to start the season or something, so it became a pretty easy decision at that point."

Sullivan was promoted to the parent club after the Penguins stumbled through the first two months of the regular season, and has been there ever since. And might well remain for quite a while.

"Whoever the next coach is, it's going to be hard to replace Mike Sullivan, whenever that time comes," Rutherford said. "Whether it's two years from now or 20 years from now, it's going to be hard to find a better coach than Mike Sullivan."

____________________

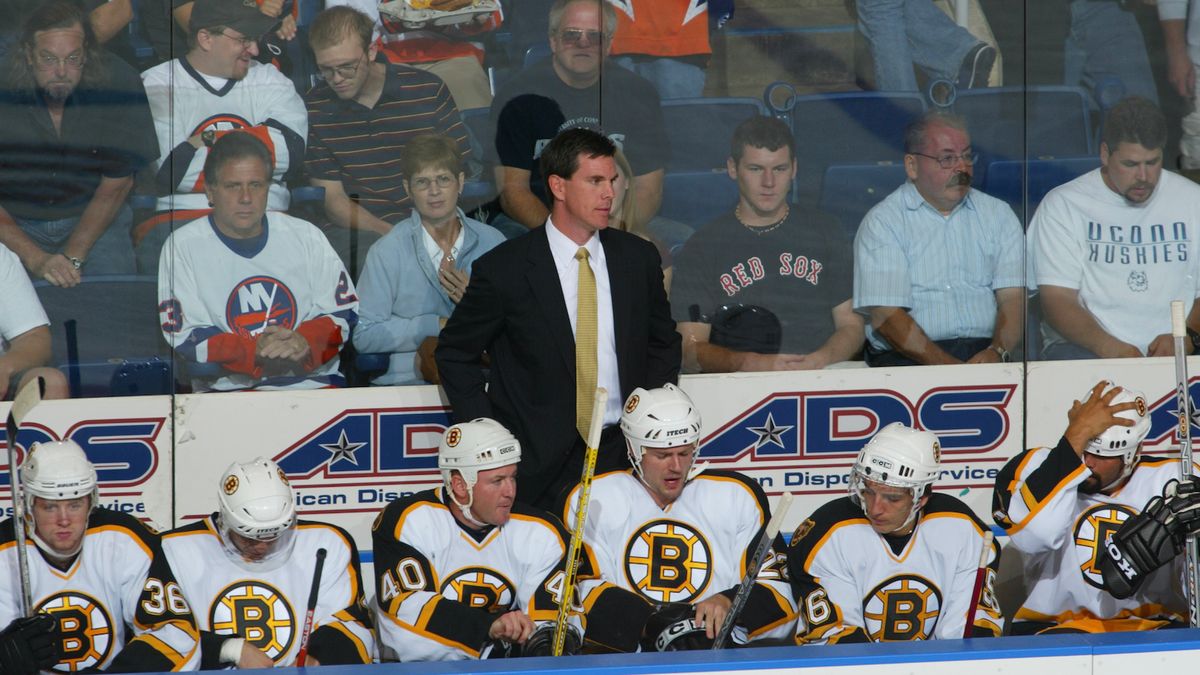

GETTY

Mike Sullivan behind the bench as the Bruins head coach

It's not a lack of hockey knowledge that causes coaches to lose their jobs at this level.

When someone is hired to coach in the NHL, it's a given that he has a thorough command of the game and its nuances, that he's skilled with the Xs and the Os and every other letter or number that his work might require.

Of course, knowing the game isn't enough to guarantee employment for an extended period, and factors ranging from inferior personnel to inept management can cost a capable coach his job. But if a coach can't consistently get his message through to his players, regardless of the reason, he is professionally doomed.

"If you lose the team as a coach and your voice goes dead on them, you're screwed," Guerin said. "It is such a team sport. It relies so much on chemistry and messaging and all that stuff that if a coach loses his voice and loses the room, it's impossible to move on."

"Losing the room" is a fairly common occurrence in hockey, when players simply begin to tune out what they're hearing from their coach.

"There are lots of reasons you can lose a room," Burke said.

The first he cited is when a team executive gets an unhappy phone call from a player's representative.

"The agent complains to you," Burke said. "He'll say, 'This guy isn't doing a good job.' The first guy, you tell him to get lost. The second guy, you tell him to get lost, but you think that maybe there is a problem. The third guy tells you that, you start thinking, 'Maybe there's a problem.' Sometimes, it's a splinter group within a team, that he loses a certain number of key players. Sometimes, it's a refusal to adapt to his system."

That hasn't been a concern, let alone an issue, since Sullivan joined the Penguins,

"Not even close," Rutherford said.

Sullivan's honest and ongoing efforts to connect with his players surely is part of that. So is his ability to handle the multitude of responsibilities that go with his position.

"A coach needs to be the smartest guy in the room on the Xs and Os," Burke said. "He's got to explain everything, including answering questions from players. Then you have to be able to communicate it. Then you have to be a motivator. Then you have to be a little bit of a priest, a little bit of a (psychiatrist). And you have to have good assistant coaches, which we do."

Sullivan's assistants -- Todd Reirden, Mike Vellucci and Andy Chiodo fill those roles now -- are an integral, if sometimes overlooked, part of what he sets out to accomplish every season.

"I'm trying to establish a certain level of accountability and establish a certain standard to hold everyone accountable to," Sullivan said. "I include our coaching staff as part of that."

Although players are the most important variable in determining a team's success -- the best jockey tends to be the one who has the best horse -- coaches can help to shape outcomes with things like tactical adjustments or by moving personnel into different roles to exploit a soft spot in an opponent's lineup.

Those are things at which Sullivan is adept.

"He can adjust to games on the fly, during the game," Rutherford said. "He knows when to use players, knows where to put players in the lineup, move them around. I don't see any weaknesses in his coaching."

Important as Sullivan's instincts and ability to quickly analyze on-ice developments are, the work he and his assistants put in to get the team ready before games might matter even more.

"They definitely go above and beyond to make sure we're well-prepared and give us all the things we need to know going into a game," Crosby said.

Recchi described Sullivan's preparation as "unbelievable," and launched a thorough explanation quicker than one of those lethal off-wing wrist shots that helped to get him into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

"You know exactly what you have to do for him," Recchi said. "He's extremely prepared. After games, he does the video -- he loves to do the full video -- and then we talk about it in the morning. His game-day, it's like, 'OK, this is how we're going to do it,' and he doesn't stray from it. It's very detailed. ... He lets the assistants do their jobs, and prepare. Obviously, you go through (your information) with him before we show the players. He's just very diligent about everything."

Sullivan's body of work earned him a gig as coach of Team USA at the 2022 Olympics, and is part of the reason the Penguins have stretched their streak of playoff appearances to 15 years, longest active one in the NHL.

That run, of course, will end someday, just as the franchise's streak of sellouts did recently. But what isn't likely to change anytime soon will be the passion and commitment Sullivan brings to his work. And the impact he has had during his first six years as coach will be indelible and enduring.

"This team has been successful since Mike Sullivan got here," Burke said. "That's no accident."