Before the Golden Knights came into the league in 2017, expansion teams historically struggled in their first years in the league.

The Golden Knights were the first expansion team ever to finish with a record over .500 in their first season, going 48-21-7 for a .678 points percentage. Before 2017, the most successful first-year expansion team was the Panthers in 1993-94, just narrowly missing out on a .500 season with a 33-34-17 record and a .494 points percentage. The next three most successful expansion teams were the Flyers, Kings, and Blues, all members of the 1967 expansion class.

Why were previous expansion teams so bad?

Money, mostly.

The last expansion before 2017 was in 2000, when the Blue Jackets and Wild came into the league? Their expansion fee? $80 million.

The Golden Knights' expansion fee? $500 million.

The Kraken's expansion fee? $650 million.

With that comes more pressure to put together a winning team and to do so quickly. And since teams are paying such a hefty price to enter the league, the NHL's rules surrounding expansion drafts have evolved to make their entries much easier.

Since the 2000 expansion draft, the league has also implemented a salary cap -- with that comes a salary floor -- which forces some level of parity throughout the league. Players like Marc-Andre Fleury are made available due to cap constraints.

In the pre-salary cap drafts, it was more common for expansion teams to draft cheaper, no-name players from teams. There are several examples of that alone in the history of Penguins players chosen in expansion drafts. The first player the Penguins lost in 2000 was Jonas Junkka, who was drafted in 1993 but had never even moved to North America in the seven years the Penguins owned his rights. In 1999, the Thrashers took Maxim Galanov, who was in and out of the Penguins' lineup in the one year he was in the organization. In 1993, the Panthers chose Paul Laus, who had spent the previous three years in the IHL.

I could go on.

In 2000, both the Blue Jackets and Wild only saw 11 of their 24 expansion picks even play for the team at the NHL level.

That's just not going to happen with expansion teams in a salary cap era anymore.

The timing of the expansion for both the Golden Knights and Kraken also set them up for success.

The NHL previously had rapid periods of expansion. The 1970s saw four expansion drafts with 10 teams coming into the league. The period from 1991-2000 had six expansion drafts with nine teams coming into the league. Expanding that quickly led to a weaker talent pool from which to choose from. That was perhaps most true in 1974, when the incoming Capitals and Scouts entered a league that had already added four other teams in the last four years, all while losing talent to the growing WHA. The inaugural Capitals team still holds the record for the worst record in league history, going 8-67-5 for a .131 points percentage.

When the Golden Knights came into the league, it had been 17 years since the NHL had last expanded, the longest such period in the league's modern era. The talent pool was stronger than ever.

Of the NHL's 11 expansion drafts before 2017, only two included just one team coming into the league at a time -- 1998, when the Predators came into the league, and 1999, when the Thrashers joined. Constructing a team through the draft was made much more difficult when multiple teams were doing it simultaneously.

The Golden Knights had -- and now the Kraken have -- the benefit of months of pre-scouting and building draft boards and the ability to construct a team identity without having to worry about another team being a factor.

The rules surrounding protected lists are vastly different now, too. The protected lists for the Golden Knights and Kraken drafts are the same -- one goaltender plus either eight skaters regardless of position, or seven forwards and three defenseman. Teams will lose good players.

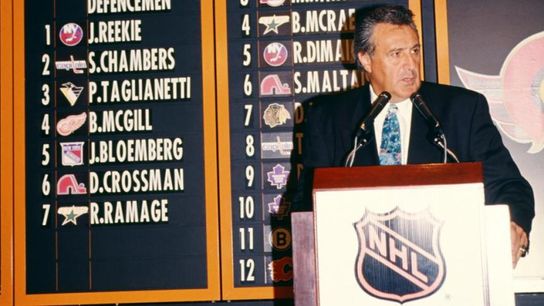

Looking back at the history of expansion draft rules over the years, previous expansion teams had it much harder with existing teams having bigger protected lists:

1998, 1999, 2000: Teams could either protect one goaltender, nine forwards, and five defensemen OR two goaltenders, seven forwards, and three defensemen

1993: Teams could protect one goaltender, nine forwards, and five defensemen

1992: Teams could protect two goaltenders and 14 skaters of any position

1991: Teams could protect two goaltenders and 16 skaters of any position

1979: Teams could protect two goaltenders and 15 skaters of any position

1974: Teams could protect two goaltenders and 15 skaters of any position

1972: Teams could protect two goaltenders and 15 skaters of any position

1970: Teams could protect two goaltenders and 15 skaters of any position

1967: Teams could protect one goaltender and 11 skaters of any position. After established teams lost each of their first, third, fourth, seventh and subsequent players, they could add an additional player to the protected list.

Not only were the lists bigger, but they often offered more flexibility when it came to the number of players by position that teams could protect.

One of the biggest challenges for earlier expansion teams in those previous expansion drafts was the ability of existing teams to protect two goaltenders in most years. Expansion teams had to find their No. 1 either by picking over teams' third goaltenders, or paying a price for a better goaltender in free agency or on the trade market. With teams only able to protect one goaltender in 2017, Vegas got a future Vezina-winner. Looking at the goaltending options for Seattle this time around, they'll have some pretty good options from which to choose as well.

It would be unreasonable to expect that the Kraken would have the same success that the Golden Knights did in 2017-18, with a trip to the Stanley Cup Final. But the days of expansion teams poaching other teams' no-name players and hovering around the basement of the league standings are over.

The Penguins and 29 other teams will likely lose a good player in the draft. And the Kraken will likely be a pretty good team.