My mom was a good writer. And I know only partly because she said so.

She wrote from the heart, often crying as she'd scrawl out her raw feelings on rolled-up yellow notepad paper, after which she'd share that work with tens of thousands of Pittsburghers every Sunday for 40 years on local radio.

I used to find this weekend ritual unsettling, even unnerving. One section of our house, held up by walls of vinyl, was known as the Music Room. None of us spent much time there, but she'd go each Saturday evening, coffee in tow, headphones up, a beautiful Serbian folk tune spinning on the turntable, and she'd read letters from listeners. Out loud. Occasionally, those letters described lost loved ones. And she'd cry. Vocally. From her core. She made their pain her pain. She made their joys and triumphs her own.

And then, the next day, she'd show up at the WPIT-FM studios Downtown and ... well, air it out. Tears and all.

I'm crying now. Vocally. From my core.

Vlatka Zgonc, my mom and the hostess of popular programs that touched Serbian-Americans and other immigrants from the former Yugoslavia beginning in 1977, passed away peacefully and of natural causes Wednesday night in Monroeville. She was 76. She's survived by my family, as well as that of my brother, Zoran Zgonc.

She's also survived by extended family in Serbia, as well as her extended-extended family of listeners across Western Pennsylvania.

She was unsettling, even unnerving. As my cousin Kika spoke to me long-distance from Belgrade on this day, she was jaka žena, which is Serbian for 'strong woman.' Only you had to hear the awed way in which Kika spoke the term to fully absorb her meaning. My mom was a strong woman back when such a thing was only morphing into reality. An overwhelming, commanding presence in every walk of life.

She'd tick some people off, but she'd get her way.

Vlatka Zgonc in 1968.

As a young woman with the brains and beauty to match her movie-star elegance, she made the bold decision to leave village life in a speck of a place called Parage, population 1,300, for the big-city schooling available in the capital Belgrade. After marrying my late father, Milan Kovacevic, a diplomat there, he was assigned to the old Yugoslav consulate in Pittsburgh. Two years after their arrival, I was born here, right Downtown, in 1966.

They split when I was 6, but she stayed. The United States felt that much bigger to her, and her eyes widened with the challenge. I obviously stuck around, as well:

Mom and me, 1972.

After remarrying, she combined her passionate musical ear with a persistent homesickness to start the radio program, initially on WIXZ-AM in McKeesport. (The slot right after Stan Savran's show, which is how I met Stan as a child.) The show grew to levels that are, honestly, hard to fathom today. The diaspora of Eastern Europeans in our region was thicker than the smoke back then, and her show was among several of its kind, most of them airing Sundays, that were seen as must-listens by immigrants, regardless of generation.

And this wasn't radio the way we think of it now, at least not for her. It was like inviting a friend to the table. She heard that all the time from her listeners: She didn't speak to them. She sat with them. This warm, wonderful yet authoritative voice was welcomed into their homes, sharing music, thoughts and, on at least one occasion, investing the entire hour of her show in song without saying a solitary word just because it felt right.

She made a connection.

She did all of it her way, too. She never answered to a company or a station. She never wavered in the face of criticism from her more organized competition. And later on, when she'd invite star musicians from Serbia to hold concerts here or she'd arrange festivals that'd draw 20,000-plus people, she was always the boss. The same applied when she opened her own boutique on Walnut Street in Shady Side, initially called Selo Fashions, then simply 'VLATKA.' No chain. No affiliation.

And through all of this, she and my late stepdad, Bob Zgonc, kept our home open -- literally, the door to our house was never locked, and people would just walk in -- to newcomers from Eastern Europe into the region. They'd hear about my Mom from this person or that person, and everyone knew they'd find a fast friend and a helping hand by coming our way.

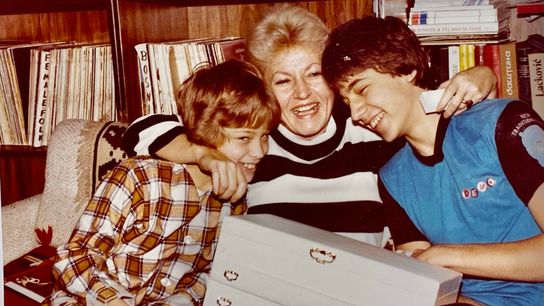

She also was a loving mom. No, an engulfing mom, the way a Serbian mom rolls:

Zoran, Mom and a geek in a DEVO tour shirt in 1983, in our family's Music Room.

As our immigrant population faded over the years, so did her show, though she kept it going for as long as the letters kept coming. Her impact on our community was profiled on our local TV stations, in the Post-Gazette, in the Tribune-Review and, as recently as this past August, in this in-depth piece by the journal Serbian Diaspora.

Mom had a rough go of it for a while leading up to her passing. Multiple health problems were compounded by fending off coronavirus a couple months back and, way more troubling for her, she couldn't be at her home, in her Music Room, anymore.

But on this Wednesday afternoon, I was supposed to drive her to a dentist. Nothing, as far as we knew, was amiss. Until it was.

This past Christmas, we visited her -- my immediate family, meaning Dali, Dara, Marko and I -- at the place she was staying for treatment. We weren't allowed inside because of coronavirus precautions, but she was on the ground floor, so we met her safely at a cracked window. The snow was coming down, everyone was smiling and laughing, and we gifted her a mini-tree we'd made that had our images on the little ornaments.

She loved it. We all did.

Mom in 2020.

Before we piled back in the car, the family gave Mom and me a little extra time to ourselves. She asked how our business was going, and she did so from the perspective of being the only person on the planet who didn't think at the time that I'd lost my mind in breaking away from newspapers. I filled her in. She asked if I was working too hard. I reminded her that I was her son. She asked if I was taking care of myself. I reminded her that I was her son.

It's then that she pointed to a nearby drawer in which she said she was writing up some memoirs. Of her extraordinary life and self-carved career.

To which she'd add, in her inimitable way of reminding me that I was her son, "I'm a good writer, too, you know?"

Yeah, Mom, I know. Everyone whose name ever passed across that yellow notepad will know that.

I'm blessed beyond words to have had the chance to tell you this on that Christmas Day, but I'm proud of you. I'm proud of what you achieved. I'm proud of what you meant to so many people. I'm proud to be your son.