DENVER -- Felipe Rivero found his triple-digit fastball last fall in St. Louis. It was an October bullpen session at Busch Stadium. The final series meant nothing. The risk was negligible. And with coaches and a couple teammates keeping a close eye, he reared back and let it fly.

Boom. Right where Heberto Andrade, the bullpen catcher, had placed his mitt.

Rivero took it out to the real mound later. And the radar gun didn't lie: 101 mph.

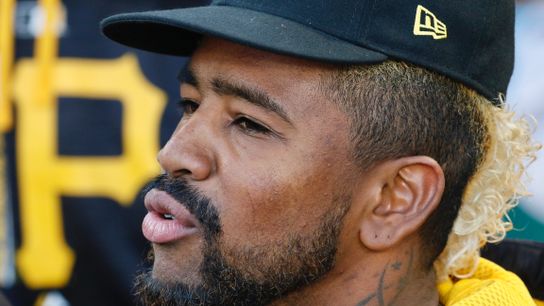

"It was the first time in my life at 100," Rivero was recalling for me Friday at Coors Field before the Pirates' 13-5 romp over the Rockies. "I never wanted to push like that because I didn't know if I could control it. But when I did it, I let go ... oh, that felt so good."

And thus, a lights-out reliever was born.

Or not.

"The fastball is a beautiful thing. And a fastball that comes in 97-101 with a tail, that's the best thing in baseball," Ray Searage was saying. "But when you've got that plus a pitch that no one can recognize, much less hit ... I don't even have words for that. I really don't."

Magic, maybe?

"Maybe."

____________________

Rivero found his magic at age 17, on a weed-strewn sandlot in the Venezuelan industrial town of Guacara. And he found it by doing things all wrong.

Jorge Moncada, now the minor-league pitching coordinator for the Rays, coached their Venezuelan Summer League team at the time. This was 2008, shortly after Rivero had been signed as a baby-faced, wiry-framed international free agent, and his fastball could peak at an impressive 84-85 mph.

"That was great," Moncada was recalling for me in a long phone talk Friday. "But it's the only pitch he wanted to throw. He could get everybody out, but he wasn't going to get better."

Before one game, Moncada introduced the standard changeup to Rivero. Fingers on four seams. Same arm action. Release, and watch the ball drop below the bat.

Only Rivero's didn't drop.

"So bad. So straight," Rivero said. "I tried and tried. No action."

Discouragement is dangerous for a pitcher so young, no matter his arm strength, so Moncada wanted to rewrite the script before it could settle. He stepped to the mound, put his hand on Rivero's shoulder and instructed him to try a two-seam grip, the least common among the many changeup grips. A two-seam grip is best associated with the sinker, and the velocity on that pitch tends to be much closer to that of a fastball. But the primary purpose of the changeup, which comes with distinct pressure and release points, is to look like a fastball in all forms while arriving much later.

This was a risk, too. But not for long.

"The first time I tried it, it was good," Rivero said, motioning downward with his left hand to illustrate the decline. "It felt comfortable."

"Maybe it was his arm slot that didn't work with the four-seam, maybe some guys have better feeling with the two seams," Moncada said. "But it just happened for Felipe. I had to push him for a while. Remember to use it. He was a very smart kid. He always listened to me, but it was more about trust in the pitch. When he started to get swing-and-misses, he knew the magic begun."

Magic?

"For sure. Because the pitch started to do more when he got back to it."

Two years ago, now in the Washington system, after years of being dormant -- relievers in the minors almost always are instructed to focus on two or three pitches and no more -- the changeup was resurrected. And this time, with his frame no longer the 145 pounds Moncada remembers from Venezuela and his arm strength becoming elite, the movement was something else. He didn't always know where it would move, but it sure moved.

Show that to an instructor in any system, and they'll gush first, worry later.

"I wasn't very confident where it would go, but I got a lot of swings-and-misses because hitters didn't know, either," Rivero said with a small laugh. "I didn't use it too much."

Once promoted to Washington, he'd occasionally work one into the repertoire in a safe count. The result was much the same. Batters didn't know, either, so they kept swinging, kept missing.

Still ...

"I gave up hits. I threw it in the bullpen, not so much in games. I used the fastball and slider. Hitters knew what was coming."

And after Neal Huntington and staff acquired Rivero for Mark Melancon at the trading deadline last summer, the movement to more changeups was inevitable. Searage is a proponent of having all his pitchers, even relievers, utilize the changeup, mostly so that they always have "that one extra weapon in their back pocket," as he put it.

Whether or not the GM and staff were aware the changeup was this good is conjecture. On the day of the trade, in Huntington's conference call with reporters, he spoke almost entirely about the fastball while adding that the Pirates had "hope" for Rivero's breaking ball and changeup. Speaking only for myself, I never heard anyone in the organization mention the changeup with any conviction until this past spring training in Bradenton. And that's understandable, given that it really began to blossom in its current form down there.

That's because Searage wanted to see it. A lot. And to that point, he wasn't entirely sure what he was witnessing.

"I thought, 'It's like a changeup,' " Searage said.

"Ray thought it was a splitter," Rivero said, grinning. "So when he saw me throwing it after I told him it was a change, he went, like nuts."

____________________

Here it comes, the changeup all grown up. But you can't hit it.

This was July 5 in Philadelphia, where Aaron Altherr might as well have been blindfolded:

This was July 14, and I can only presume that the PNC Park grounds crew was able to repair the corkscrew damage caused by the Cardinals' Stephen Piscotty:

This was Monday, when the Brewers' Jonathan Villar rolled over an inning-ending grounder to strand a man at third with a one-run deficit in the eighth inning:

There was no shame in any of these at-bats, mind you. That's what I learned upon surveying roughly a third of the visiting clubhouse Friday, as Rivero's teammates raved not only about the changeup, but also how the fastball sets it up by being 10-plus mph faster, how his arm slot and progression through the delivery stay identical for both pitches, how the changeup curls in under the arms of left-handed batters, how it can be used in any count and any situation and ... oh, I'll just let them talk.

"It's crazy," Gregory Polanco said. "You can't lay off it. You can't hit it. What do you do?"

"It feeds off the fastball," John Jaso said with a slightly more analytical bent. "The fastball comes in so hard that you can't sit on it, even though you need to, because ... you know, it's coming at 101. So if you're set for that, and this thing comes, then it dives off to the side ... I give our catchers a lot of credit. They've handled it well. You see against a free-swinging team like the Brewers where our catchers were starting off everybody soft, then coming hard. Once you get them going with that long swing, you go at them with the heater."

Jaso's locks shook as he paused.

"It's silly, man. It looks absolutely silly watching guys trying to do something with it."

The men at the receiving end expressed similar sentiments.

"I know exactly how it works," Chris Stewart said. "I call for the pitch, they swing and miss, and I call for it again."

"This guy ... he throws 100, and then he slows it down, and then it moves like crazy," Francisco Cervelli said. "You go up there, facing a guy like Rivero, and what are you thinking? Fastballs, right? But the speed is so different."

Cervelli motioned across the clubhouse toward Rivero's stall.

"This guy was born with something special. He's showing that to the whole baseball world now."

One could hardly argue that:

"It's like Aroldis Chapman," Cervelli continued. "You see one of those guys in baseball maybe one every five years. That's what we've got. We've got that guy. And he's going to be great."

____________________

Giving rise to something great, as Moncada did, and keeping something great -- the very essence of a sport evaluated forever upon consistency -- can be two very different tasks. Rivero's success, as we're seeing, is rooted in far more than the fastball or changeup or even their fatal combination.

"I'm having fun," Rivero said. "The most fun of my whole life. I'm going out there pitching, getting hitters out, helping my team win ... every day feels like a good day."

That's the start. It's got to come from within.

But his support staff still includes Moncada, as the two still text regularly, and Moncada is so moved by Rivero's many achievements that he'll tweet them out on his personal account.

"Every day he becomes more special," Moncada said. "I'm proud of him."

Searage, too. Rivero divulged that "almost every morning" Searage will send him a text with words of encouragement for the day, as well as a very brief bit of advice related to pitching. Something about locking in his arm angle. Or about a batter's tendency.

Nothing about the changeup, though.

"It's beyond any of us to control that thing," Searage would say, "That comes from a higher power."