As the Steelers have made a clear intention to use the bye week to take a good, long look at their shortcomings in the running game, there's a debate that continues to command chit chat at the water cooler or arguments on social media: Najee Harris or Jaylen Warren?

The goal of this edition of Chalk Talk is to truly dive deep into the film, as well as both traditional and advanced stats, to determine what the best course of action should be for Matt Canada's offense going forward. Is Harris still the clear No. 1 guy? Should Warren supplant Harris as the team's lead running back? Or, should the Steelers deploy these two as a legitimate 1-2 punch?

First, and this really can't be stated enough, the offensive line has simply not been good enough to support a formidable running game. At the end of the day, the line's poor play, especially in the first two or three weeks of the season, was simply not good enough. It really didn't matter who was running the ball. The blocking was so inconsistent and poor, debating between Harris and Warren was truly a waste of time, breath and energy.

Above anyone else on the offensive line, Mason Cole has been a huge disappointment. He was a serviceable center in 2022, and also added the intangible of being a great leader in that room. However, on-field performance is ultimately what matters. Cole is missing assignments far too often or simply getting pushed straight backwards:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

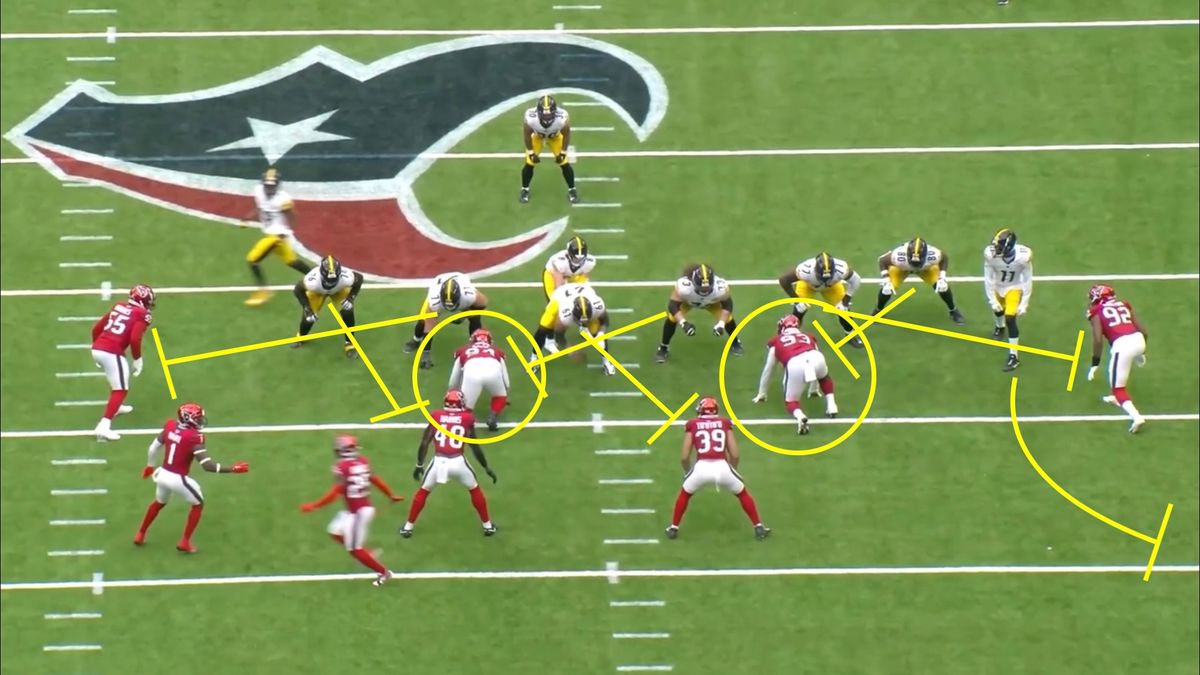

When talking about the running game, the offensive line has to be part of the discussion. Whether it's Harris or Warren, running the ball has not been the easiest for either back, especially when tight ends are also getting pushed into the backfield:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

What's Harris supposed to do here? Darnell Washington is essentially in Harris' lap by the time he receives the handoff. That's not the running back's fault. And, with Pat Freiermuth out for the foreseen future after aggravating his hamstring injury, more responsibility will be put on Washington, Connor Heyward and Rodney Williams. Tight ends are just as important as the offensive line to the running game, especially with the way the Steelers like to run the ball (more on that later).

But, outside of the blocking up front, there are some areas where we're seeing similarities and differences between Harris and Warren, both good and bad. This is best exemplified by showing how each running back attacks the same play.

One go-to running play in Canada's playbook is the Steelers' version of "crunch," where the crux of the play is letting the 3-technique through to be "wham" blocked by a pulling tight end, as well as having the left guard move to his right to "wham" block the 1-technique on the weak side:

NFL.COM

Side note: This is a really cool running concept. Jim Harbaugh had success with this play during his time as the 49ers' head coach. Frank Reich used it when he was the Colts' offensive coordinator. It's not a play that can be called too often, but it's a nice go-to when the Steelers really, really need yards on the ground on first or second down. It's also especially effective against aggressive defensive fronts, especially since two interior defenders are left to be "wham" blocked. It is NOT ideal for short-yardage situations, given the number of players in the box and misdirection of the play. There's a time and place for it. Less is truly more with this play.

First, let's take a look at how Warren attacks this play:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

If blocked properly, he should attack the B-gap, which ends up being right off of Washington's outside hip after he makes his block. That is exactly what happens, and Warren uses his excellent burst to accelerate through the hole.

The vast majority of running concepts that attack the B-gap or anything outside of that try to give the running back one-on-one matchups with cornerbacks or safeties in space, especially the former if it can be blocked that way. Warren's skill set is great for this because his speed and acceleration forces the cornerback to make his decision faster. Does he contain the edge? Does he try to fill the gap? Allen Robinson goes up to block the cornerback here (quite poorly, I might add), but it really doesn't matter. By the time the cornerback makes his decision, Warren's already blown past him and only has the two safeties to beat. He's also one broken tackle away from a touchdown.

Now, here's Harris running the crunch play:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

One very noticeable difference before the snap: The Browns have three interior defenders and two edge defenders all up on the line of scrimmage. With five down linemen, the Steelers have to block this differently. Instead of Washington and Isaac Seumalo pulling to "wham" block, only Washington does. Seumalo then takes Cole's initial assignment to get to the linebacker on the second level while Cole blocks down on the 0-technique right in front of him.

Also, with eight defenders in the box, Robinson is primarily responsible for the linebacker lined up across from him. That way, it gives Harris the one-on-one with the cornerback. The cornerback decides to plug the gap, but Harris bounces it outside and makes the cornerback pay for his decision, and it's ultimately why the Steelers want to run more concepts to the outside with Harris.

Go back and watch the play again and look at how many more yards Harris gains after the first initial contact, which is a measly slap. Yeah, that first contact comes at the 23-yard line and Harris isn't brought down until the 40, and the cornerback even had to pull on Harris' dreadlocks to bring help bring him down.

The way both running backs attack this play is indicative of the strengths each back possesses. Warren is a better gap scheme runner. He knows the hole he has to hit, and he hits it with absolute authority. When it's well blocked, Warren could possibly make a house call.

On the other hand, Harris is a better zone scheme runner. That goes back to his Alabama days. Zone concepts aren't as simple as "see the hole, hit the hole." Specifically with outside zone, which the Steelers run more than any other concept, there's a main attack point, but then there should also be a cutback lane up the middle if the primary attack point is cut off.

As an example, watch Harris use patience to wait and see if the main attack point (between Broderick Jones and Washington) opens up:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

Harris' vision is really on display here. His primary attack point looks to be cut off at first, so he looks to the cutback lane up the middle. When Roquan Smith cuts that off, Harris goes back to attack his initial attack point to find Jones and Washington open up a hole for him. Harris hits it hard and gains eight yards. It also takes similar vision to run the crunch play above against a loaded box.

When everything is cut off, there's always the emergency cutback all the way across the play if the defense over-pursues. Harris did this against the Browns and Week 2 -- even when just about everything broke down other than Calvin Austin III's block -- and rattled off a big gain because of it:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

The numbers really tell quite the story. When Harris runs zone concepts, he's averaging 4.1 yards per carry, but only averages 3.6 yards in gap concepts. It's the opposite with Warren. He averages only 3.0 yards per carry in zone concepts, but averages 4.5 yards in gap concepts.

It's clear each running back has their individual strengths. To their detriment, the Steelers don't disguise it very well. Taking out the Week 1 loss to the 49ers (because the Steelers were forced to be one-dimensional so quickly), Harris has been on the field for 52 passing snaps compared to 58 running snaps, and Warren has been on the field for 62 passing snaps compared to only 30 running snaps. That's pretty much a dead give away of what the Steelers plan to do when either Harris or Warren are on the field.

In addition, Alvin Kamara is the only running back in the NFL that is being targeted at a higher percentage of his routes run than Warren (32.9%). Warren also averages 2.18 yards per route run, which leads all running backs in the league.

Quite simply, when Harris is on the field, the Steelers run the ball; when Warren is on the field, the Steelers pass the ball.

Now, that doesn't mean that a first-round pick such as Harris shouldn't be held to a higher standard. That's premium draft capital invested in a running back. When plays need to be made, he's gotta make them. When plays are blocked well, he needs to feast.

In particular, plays like this just happen far too often:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

... and this one from last season:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

Notice that both of these plays are also crunch. The only difference between this and Warren's run shown above is the safety is playing in the box, so the receiver (same spot as Robinson) has to block him instead of the cornerback like Robinson did. But, that's what you want here: Give the running back time and space with a one-on-one against a cornerback.

It's quite simple here: Harris has to beat cornerbacks when he has one-on-ones with them in space. He's too big and too strong to get tackled like that, especially playing in the AFC North. It comes with the territory. The Ravens, Browns and Bengals will use all 11 guys on the field to defend the run. Harris needs to win those battles when presented, much like he did in the crunch example against Cleveland. But, his experience with running zone concepts helped execute that play. When the B-gap was closed off by the cornerback, Harris seamlessly bounced outside and emphatically won the rep.

Now, you can digest this information as you wish. I'm not pushing any agenda here. But, based on the film and the data, it would behoove the Steelers to stick with a 1-2 punch, Harris being the lead back. Just because Warren can run crunch better than Harris doesn't mean he's the better back. That's one play in playbook full of running concepts. Harris is still far and away the better runner in zone concepts, and that's the current playbook. Once there's a new offensive coordinator with a new playbook, then we can revisit this debate.

Also, any perception that Harris vastly outplays Warren just isn't true. These guys both get their fair share of playing time now. Harris' 161 snaps isn't that much more than Warren's 137 snaps. The disparity in rushing attempts (Harris' 63 carries to Warren's 34) is simply because Canada and the coaching staff truly have important roles carved out for both guys tailored to what they believe is best for each player.

What we probably need to see is more packages where they are on the field together:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 8, 2023

They've really only done this in their last two matchups against the Ravens. Try it out on some other teams, please.

These two guys truly have their respective strengths and weaknesses. Harris can certainly hit another level. There's no doubt about that. And, when we've seen Harris play at his best ... man, he's dangerous. He just looks unstoppable:

— DK Pittsburgh Sports (@DKPSvideos) October 18, 2023

Warren's a great receiver for Kenny Pickett, but he still has room to grow as a runner. He's also not built for a heavy workload running between the tackles. Harris averages nearly a yard more per carry after contact. Warren does his best work in space.

In addition, Warren just doesn't see the same defensive fronts that Harris does. As telegraphed by the snap splits, the Steelers throw the ball twice as often as they run it when Warren is on the field. That trend forces opposing teams to deploy packages that are tailored more for defending the pass. It's certainly easier to run against lighter boxes and lesser guys up front.

In my professional opinion, these two are best used when complementing each other. Harris has power and strength, coupled with enough athleticism to play a role in the passing game. Warren is a great third down back that can be a checkdown on any play. But, he also shown enough skill as a runner to earn more actual carries and spell Harris for an entire series here and there.

The Steelers haven't had a legitimate 1-2 punch since Le'Veon Bell and DeAngelo Williams. They have one now in Harris and Warren. It's up to the offensive line to block for them, and for the coaches to come up with a formula to best utilize both backs.

The bye week did wonders for the running game last year. Production on the ground jumped around 50 yards per game afterward. This year, the team is seemingly taking a similar approach. Harris told reporters this past week that he and Cole stayed extra days to watch film and discuss what each one is seeing to get more in sync. Warren talked about adjustments being made to the offense's alignments to better set up blocks -- "similar" stuff to what they did last year.

All of that is encouraging news. It acknowledges that no matter who is running the ball, this team is not doing nearly enough on the ground. If the offensive line gets better and more consistent at opening up holes for Harris and Warren, then we can return to the debate. For now, it's about getting both of them going on the ground, not one or the other.