WARREN, Ohio — The ceiling inside of the Buena Vista Cafe barroom is a work of art on the level of the Sistine Chapel. At least for those who worship and mythologize high school football around these parts.

The squat one-story restaurant, tucked into an East Side residential neighborhood, has been serving meals to Harding High School football players since Hall-of-Famer Paul Warfield was thrilling crowds at nearby Mollenkopf Stadium in the late 1950s. The walls are filled with autographed jerseys of collegiate and NFL stars. The shelves are lined with helmets from every level of the game.

But patrons dining on Greek fried chicken and greens must look up to see the marquee attraction — the Mollenkopf Stadium field painted in vivid detail, complete with goal posts hanging upside down from the ceiling. The arresting image is a point of pride for citizens in this small Northeast Ohio city, which has hemorrhaged manufacturing jobs since the late 1970s.

Steel mills have been shuttered. General Motors has abandoned the area. Yet through all the economic downturns, Warren has been harder to kill than Rasputin. No place is the indomitable spirit more vibrant than at Mollenkopf Stadium, where the assembly line keeps producing pro players unabated. Warfield. The Browner brothers. Mario Manningham. Korey Stringer. More than 40 players have reached the NFL from either Harding or the former Western Reserve High, a staggering sum for a town that punches above its population weight class of 39,000 residents.

Few have a backstory as unusual or as intriguing as Steelers’ free-agent acquisition James Daniels.

Like so many old Rust Belt communities, a lot of people leave Warren searching for success never to return. The Daniels family, however, circled back. LeShun Daniels Sr., an integral member of the 1990 Harding state championship team, made his mark in Columbus, Ohio and in other cities across the Midwest before coming home in 2011. It allowed James and his older brother, LeShun Jr. to marinate in the school's preps-to-pros broth while playing in front of extended family.

Some of the lessons the versatile offensive lineman will bring to the Steelers this fall were learned on the city's gridiron and in its classrooms.

“When we found out LeShun was coming back, people were really happy,” said Buena Vista owner Nicky Frankos, an assistant coach on the 1990 state title team. “It’s a great family that has its priorities straight, and we knew their sons would help the football team.”

TOM REED/DKPS

The painting of the Mollenkopf Stadium field is among the most arresting visuals inside of the Buena Vista Cafe.

The Daniels aren’t quite the Browners, who sent four family members (Ross, Joey, Jimmie, Keith) to the NFL, but LeShun Sr., James and LeShun Jr., all reached the game’s highest level.

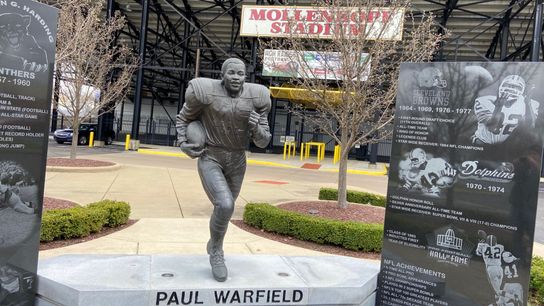

The Steelers are hoping James, 24, who signed a three-year $26.5 million deal, blossoms into a standout worthy of a statue alongside the one dedicated to Warfield, which stands sentry outside of the stadium.

“(Warren) means everything,” LeShun Sr. said. “It’s a hard-working, blue-collar town. Some of the industries have left, but there’s still a standard for hard work. We’ve been blessed to move around to different parts of the country, and I thought it would be a good environment for our kids to go to school.”

____________________

Korey Stringer knew his audience. The former Pro Bowl offensive tackle recognized the value his best friend, LeShun Sr., and his wife, Alicia, placed on education. So when “Uncle Korey,” another member of the 1990 Harding title team, came bearing gifts for Christmas and for birthdays they were never toys. They were always books to feed the imagination.

Among James Daniels’ best attributes is his mind. It helped earn him early success as a 17-year-old starter for the University of Iowa and as a 20-year-old regular contributor for the Bears. Saying James has a “high football IQ” doesn’t do justice to his range of intelligence. He possesses a natural curiosity about the world that was instilled in him by his parents.

Both his football coach and his math teacher at Harding describe him the same way: A natural-born problem solver eager to learn.

“Both James and his brother were among my top students when I had them,” said Tom Burd, who had the Daniels brothers in his pre-calculus class. “Their level of preparation showed up really quick.”

James’ ability to make calls and adjustments along the offensive line with the Bears was evident even as a sophomore starter for Harding in 2012 when he opened holes for his brother, the Raiders’ star running back, who's two years older.

“He’s very smart in his ability to pick up new stuff and be able to apply what’s he learned,” longtime Harding football coach Steve Arnold said. “When he went to Iowa, he would call back home as a freshman and tell me about things they were running offensively and how we might be able to do the same things here at Harding. He was 17-years-old!”

TOM REED/DKPS

Warren Harding football coach Steve Arnold stands next to a photo of James Daniels blocking Aaron Donald.

Alicia and LeShun Sr. met at Ohio State, the latter being a part of an outstanding Buckeyes offensive line that featured Stringer and future Hall-of-Famer Orlando Pace.

Even with the opportunity to play on Sundays — he appeared in one regular-season NFL game with the Vikings in 1997 — LeShun Sr. understood the importance of getting his college degree in history. He eventually earned an MBA, embarking on a career in business that has him working as a district manager for a national vending and hospitality company.

Alicia serves as a human relations specialist for the Library of Congress after serving as an administrator for the U.S. Census Bureau. The couple now resides in suburban Washington D.C.

“Education played a huge role in our household,” said LeShun Jr., who earned a degree in health and human physiology at Iowa. “Our dad used to tell us about when he was growing up and the people who had all the ability in the world, but when they lost sports and that athletic ability, it was hard for them to get reacclimatized to the real world.”

Everything in the Daniels’ household was a competition. James and LeShun Jr. battled for top honors in football, the most medals at track meets and the best grades in school. Their education didn’t stop at the sound of the day’s final school bell. Alicia set up math flashcard contests and had the boys working on projects involving Black History Month and women’s studies.

The television sets in their home were tuned to news programs, especially during the dinner hour.

“When they were little, we always watched the news together,” Alicia said. “If there was something going on in the world, they were aware of it and we would have talks about it if they didn’t quite understand something or wanted to know why something happened.”

Even the tragic death of Stringer — he died from complications related to a 2001 training-camp heat stroke with the Vikings — served as a teaching moment. LeShun Sr. made sure his two oldest sons were cognizant of hydration during practices and staying in shape year-round.

The kids spent their early years living in DeKalb, Illinois, LeShun Jr. burgeoning into an excellent running back and James showing promise as a lineman.

Dad couldn’t offer much insight into ways of juking linebackers and defensive backs, but he supplied plenty of real-world experience for James, the backyard turning into a gridiron classroom and laboratory.

“I was just making sure his angles and steps were right,” LeShun Sr. said. “He’s a naturally gifted offensive lineman. He can do some things at center that remind me of Pittsburgh Steelers great Dermontti Dawson, who was probably my favorite player.”

Every task came with a purpose. LeShun Sr. wanted the boys to compete in track and wrestling, which he believed would benefit their football careers. The explosive steps and balance required to throw a shot put also enhanced James’ ability to fire off the line of scrimmage.

“James is a technician,” Arnold said. “Back in high school, he didn’t look like an Ohio State- or Alabama- or Iowa-type of lineman. But he was so technically sound and he played so hard and he had those long arms. He was just a natural without the imposing figure.”

____________________

KARL ROSER / STEELERS

James Daniels runs through drills on the South Side

Warren is a comfort-food lover’s dream and a cardiologist’s nightmare. The chicken wing is considered a fifth food group here and the competition is so robust that Hooter’s failed after six months in town.

James, like many of the natives, packed on the pounds at the Sunrise Inn and the Hot Dog Shoppe, whose “spinning weenie” atop the restaurant is a Warren landmark.

“The food there was so good,” Alicia said. “James loved the hot dogs and the fries with chili and cheddar on them.”

LeShun Sr. moved his family back home to be closer to his aging mother, allowing her to see the kids before they went off to college. His daughter, Skyler, is a junior at Ohio State and the youngest son, Ellis, is a 14-year-old offensive lineman in training.

Although not the primary reason for their relocation, LeShun Sr. knew prep football in Northeast Ohio was a step up from the competition in DeKalb. Among the many highlights was getting a chance to watch James block for LeShun Jr., who rushed for 1,612 yards as a senior.

“Seeing them play together at Harding brought back a rush of memories and good times,” LeShun Sr. said. “Football is big in the Chicago area, but I still don’t think there’s anything like football in Northeast Ohio.”

The Raiders went 9-2 in 2012 only to have their season ended at the hands of James’ future NFL teammate. Mitch Trubisky, who was Ohio’s Mr. Football, led Mentor High to a 42-35 playoff win in which he accounted for 450 yards of total offense and six touchdowns.

“I’m always happy to see players from Northeast Ohio do well,” said LeShun Jr., who rushed for 219 yards in the loss. “It was unfortunate things didn’t work out in Chicago for him, but I am really excited to see how he’s developed since those days. Because I do think he’s a talented player so I’m hoping that he shows the league that. He also needs James to help lead that offensive line to block well so Mitch has that opportunity.”

LeShun Jr. chose to attend Iowa, where he rushed for 1,058 yards and 10 touchdowns as a senior before playing four games with the Washington Commanders in 2017. Meanwhile, James developed into a terrific interior offensive lineman at Harding, drawing scholarship offers from Alabama and Ohio State. Given his love for the Buckeyes and his parents’ history at the university, most in Warren assumed James was headed to Columbus.

His Harding football coach thought otherwise. During the recruiting process, Arnold slipped a note into James’ file with his prediction on where the lineman would attend college.

“He always wanted to see it,” Arnold recalled. “I said, ‘I’m not going to let you see it because I don’t want to influence you.’ Once he committed, I showed him the piece of paper that said ‘Iowa.’ I just figured the chance to block for his brother again would win out.”

Iowa boasts a rich tradition of sending linemen to the NFL, and in 2015 James became the first Hawkeye to start as a true freshman on the offensive line since Bryan Bulaga in 2007.

Former Hawkeyes assistant coach Tim Polasek marveled not only at James’ athleticism, but his grasp of offensive intricacies.

“I sat in with him on a couple of interviews during the NFL Draft process,” said Polasek, who’s now at Wyoming. “He was able to take the concepts we were doing at Iowa with the directional calls and the (linebacker) identifications and he was able to apply it to a couple different NFL teams really quickly in the interview sessions. His football acumen is off the charts.”

____________________

ALICIA DANIELS

The Daniels family celebrates James (center) being drafted by the Bears in the second round in 2018.

LeShun Daniels Sr. united the Warren football community. His son James is about to drive a wedge through it.

In 1990, the two Warren public schools consolidated, creating animosity on both sides of town. The rivalry between Harding and Western Reserve was so fierce that some fans took to using rulers to measure story lengths in the Warren Tribune-Chronicle to make sure their side earned equal coverage.

LeShun Sr. and Stringer helped bond the city by going 14-0 and winning a Division I state title in the first year of the consolidation.

However, there’s still a football rivalry that plays out 365 days a year in Warren, and James’ decision to sign with the Steelers will only intensify it. The city is roughly equidistant between Cleveland and Pittsburgh, and Warren is where the grievances between the fan bases are the loudest.

“When my brother, David, was drafted by the Steelers, people all of a sudden were mad at me,” Arnold said laughing. “I’m like, ‘What did I do, he got drafted?’ The hatred runs deep.”

James was asked about the animus a few weeks ago, and wisely stayed above the fray by noting he was only a college football fan while living in Warren.

As for his father, well . . .

“I was a Browns fan growing up,” LeShun Sr. said. “It’s going to be a big culture shock for me to start cheering for the Steelers. I loved Bernie (Kosar) because he grew up in Boardman and I loved (Eric) Metcalf, Ozzie (Newsome) and (Earnest) Byner.”

TOM REED/DKPS

The statue of Hall-of-Famer Paul Warfield epitomizes the rich history of football in Warren.

After four years with the Bears, James said he has no issues with where the Steelers play him on their rebuilt offensive line. He’s undoubtedly an upgrade and his versatility is coveted, having played mostly at left guard in Chicago but also making eight starts at center, the position he played at Iowa for his final two seasons.

His dad thinks center is where James will excel. His oldest brother believes he’s better suited at guard. Both agree it’s time for James to settle into one position if only to start building some continuity.

“The big fella can run block with the best of them,” LeShun Sr. said. “He can also pass block, and this offseason he’s going to work a lot on that.”

James said he can’t become a Steelers’ team leader right away, but he’s not one to keep quiet on or off the field when he sees something wrong. Two years ago, he was among several former Hawkeyes players to speak out concerning racial injustice within the Iowa program.

There are too many racial disparities in the Iowa football program. Black players have been treated unfairly for far too long.

— James Daniels (@jamsdans) June 6, 2020

“He recognized the disparities at Iowa and wanted to help bring about change,” said Alicia of her son who graduated with 3.24 GPA and a degree in health and human physiology. “He cares about Iowa. The program has moved forward with initiatives to deal with those issues.”

James, who wore black and gold in Warren and Iowa, is excited to return to his favorite colors with the Steelers. Pittsburgh is an easy drive from Warren and Washington D.C., and there figures to be plenty of Daniels No. 78 jerseys in the crowd at Heinz Field.

The owner at Buena Vista Cafe is also clearing out wall space for one in his bar.

“Oh yeah, the pride of Warren,” Frankos said. “I’ve got to get his butt back over here to bring me a jersey. That family means a lot to this town.”