COLUMBUS, Ohio — Alan Faneca is an early riser. Roosters living in the Virginia Beach region, where his family resides, could use him as a wake-up call service.

The former Steelers’ left guard attacks the day in the same manner he did defensive linemen while escorting Jerome Bettis to end zones. The next time Faneca reaches for the snooze button will be the first.

Not that Julie Faneca’s husband is getting much shut-eye, anyway. For each of the past five years, she and the kids have watched Alan grow restless as their trip to a Super Bowl host city approached.

“I do lose sleep in what I call, ‘Hall of Fame season,’ ” Faneca said Wednesday in a phone interview. “You’re trying not to think about it, but it’s this amazing honor that’s dangling out there right in front of you.”

Faneca, 44, is one of 15 modern-era player finalists for induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He’s reached this stage for a sixth-consecutive year, and among the current candidates only former Buccaneers’ safety John Lynch has been a finalist (eight times) more often.

While most football fans focus on the drama that unfurls on Super Sunday, there’s just as much emotion involved in the HOF class reveal, which occurs on the day before the game. In recent years, finalists have been asked to travel to the Super Bowl site, where Hall president David Baker has knocked on the hotel-room doors of the winners in a made-for-television event.

Those not being fitted for gold blazers are notified by phone.

“We’ve brought our (three) kids every time, and they have been in the room when we’ve gotten the phone call instead of the knock,” Faneca said. “They have gone through the disappointment as much, if not more, than I have. It’s tough when you have to get the call and then have to console three kids and a wife.

“I’ve said they should be filming what happens in the hotel rooms that get the calls, not the knocks, because it would be pure gold.”

Faneca is a six-time, first-team All-Pro. He played 13 NFL seasons, including 10 with the Steelers, and won a Super Bowl in 2005. For all the big games and pivotal moments, few have been as stress inducing as the days and weeks leading up to the Hall-of-Fame announcements. It’s a common refrain from great players hoping to receive their sport’s highest individual honor.

“Riding that rollercoaster wasn’t a pleasant experience,” said former Steelers receiver John Stallworth, who was enshrined in 2002 after being a finalist in eight of the previous 10 years. “It’s mentally draining, and it’s tough on your loved ones when you don’t get in. After a few years, I just made it a point to get off that rollercoaster and focus on my work and my family as the time for the announcement came closer.”

The agonizing wait that finalists endure is now the subject of a beer commercial. Coors Lite is championing the candidacy of Tom Flores, the first Latino coach to win a Super Bowl. Nicknamed "The Iceman,” Flores delivered two titles to the Raiders in the early 1980s, but has been obscured by more high-profile coaches in a bid for HOF recognition.

Flores gets his best shot this weekend as the lone finalist in the coaches category. The same is true for the family of the late Bill Nunn, the trailblazing former super scout of the Steelers, in the contributors category and former Cowboys receiver Drew Pearson in the seniors category. All three men will require 80 percent approval on a yes or no vote from the 48 HOF selectors. Although it’s not a rubber stamp, they won’t be pitted against currently eligible players such as Faneca.

Flores, Nunn and Pearson are likely to receive the 39 votes necessary.

“It kind of lightens things up a little bit,” Flores told the San Jose Mercury News of starring in a commercial. “If the voters haven’t made up their minds by now, something’s really wrong.”

The next 48 hours promise to be anxious ones for Faneca and the other 14 modern-era finalists. Because of the pandemic, voting was done two weeks ago on a Zoom conference call instead of at the Super Bowl host city on the day before the game.

The results won’t be officially announced until Saturday although reports of Peyton Manning’s induction in his first year of eligibility already have been leaked. That leaves four spots available for a field that’s whittled from 15 to 10 to five in three rounds of voting by the selection committee.

Once in the last group of five, modern-era candidates still need the 80 percent approval to have their likenesses made into bronze busts.

Faneca is hopeful, but history has taught him painful lessons about the need to temper expectations. This weekend, he’s not putting his kids, ages 15, 9 and 6, through the same tortuous routine.

“We used to hang out at the NFL Experience (exhibit) for awhile before heading back to the hotel to await the word,” he said. “Not this year. It’s just me and Julie heading to Tampa for a private event. We’ll see what happens from there.”

ULTIMATE REWARD

Joe Horrigan used to prep first-time HOF finalists with a devious pop quiz. The former Hall executive would ask them how many times it took legendary Steelers’ receiver Lynn Swann to gain induction — one year, two years or three years.

The players would conjure Super Bowl images of Swann acrobatically leaping over Cowboys’ defensive backs, and almost always assume he was a first-ballot member.

“I’d tell them, ‘Nope, it was in his 14th year as a finalist,’” Horrigan said.

Over the past five decades, few aspects of the NFL have grown more in stature than what it means to be a Hall of Famer.

When Horrigan arrived at the HOF in 1977, the museum’s budget was so tight its executive director had to submit a two-page memo to the board seeking permission to sell his manual typewriter to buy an electric model.

Nowadays, the Hall is big business. Rookies enter the league talking about their desire to end their careers in the Canton, Ohio shrine.

Competition is fierce, and the wait for deserving players can become maddening. In the days when Swann and Stallworth were winning four Super Bowls, the only time national-television audiences saw the new class in their gold jackets was during the halftime highlights of the annual Hall of Fame Game.

These days, the coverage is extensive on ESPN and the NFL Network. The internet teems with stories that handicap the fields and spotlight HOF snubs.

All the attention keeps great players such as Faneca up at nights.

“I try to tell the guys who are finalists that, ‘Look, this is your last stop before you make it to the Hall of Fame. The odds of you eventually making it are very good,’” Horrigan said.

But tensions can boil over. Former receiver Terrell Owens was so indignant about having to wait until his third year of eligibility that he boycotted the Hall on the day of his 2018 induction. He gave his acceptance speech at the University of Tennessee-Chatanooga.

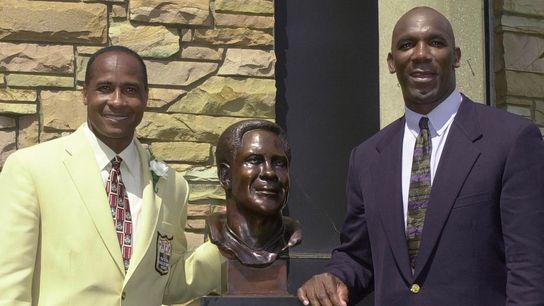

Imagine if Owens had to suffer the waits of Swann and Stallworth, whose individual greatness often cancelled each other out in the eyes of some voters. When Swann finally earned the honor in 2001, he made sure Stallworth was his presenter in hopes of elevating his teammate’s status. A year later, Stallworth returned the favor, asking Swann to introduce him to the audience in Canton.

“We had hoped we might go in together, but the important thing is we got in,” Stallworth said Thursday in a phone interview. “When I finally got the phone call, after I was done screaming and running around the house, I remembered thinking, ‘I don’ have to compete anymore. I’ve made it.’ It’s the ultimate reward.”

Swann’s election marked the first time all HOF recipients were in the city hosting the Super Bowl. In the early years, the process of notifying winners was more chaotic. Hall officials wanted the first word to come from them to ensure nothing was lost in translation.

Not that the process always ran smoothly.

In 1992, Horrigan was tasked with reaching John Mackey to deliver the good news regarding his induction. But the former Baltimore Colts tight end had not alerted anyone at the Hall he was flying to Hawaii. This was years before wireless and text messaging made communication so easy.

“I finally figured out what hotel he was staying at and left word with the front desk,” Horrigan said. “But as news got out, others were doing the same thing. When John checks in, the kid at the counter hands him all these pink slips and John says, ‘What’s this?’

“And the kid says, ‘You haven’t heard? You’ve been indicted.’ Poor John says, ‘What did I do?’”

GETTY

Lynn Swann and John Stallworth in Canton, Ohio, 2001.

PAYING IT FORWARD

Several years ago, Stallworth flew from his home in Huntsville, Alabama to Pittsburgh to attended a Steelers game and participate in a ceremony honoring past Super Bowl champions.

While at Heinz Field, the 68-year-old Stallworth spotted Faneca and asked if he could speak with him. The purpose of his visit could not have been more direct: Stallworth wanted to assure the former offensive lineman that he was Hall-of-Fame worthy.

The old receiver was taking a page from the playbook of Ken Houston, the HOF defensive back who had competed against Stallworth for years in the NFL.

“Ken had told me the same thing years earlier that I was trying to tell Alan,” Stallworth said. “He told me, ‘You deserve to be in the Hall of Fame, and you’re going to get in there one day.’ It can be frustrating, but I took great solace in hearing those words from a man like Ken Houston.”

Stallworth doesn’t envy former players still awaiting HOF validation. He’s always been a humble man, and he’s not a fan of the glitz surrounding today’s televised notifications. He does understand how Hollywood theatrics add to the special moment for those getting the good word. A year ago, Baker surprised Bill Cowher on the set of the CBS pre-game show to tell him he was being inducted.

But Stallworth also wonders how it plays for those receiving phone calls instead of knocks.

“I would not have wanted to be a part of that, sitting in a hotel room waiting,” Stallworth said.

After early rejections, the Steelers’ legend buried himself in work on the days prior to Hall announcements. In 1986, Stallworth founded a company in his hometown that specializes in providing engineering and information technology services to government and commercial clients. Ironically, the person who broke the news to Stallworth about his 2002 induction was a company IT worker who had seen a media report.

“Living in Huntsville at that time nobody was really talking about the Hall of Fame,” Stallworth recalled. “In January, the only football they were talking about was Alabama and Auburn recruiting. I liked it that way.”

Faneca tries to keep his mind occupied on other matters, as well. He recently started a business with his brother-in-law. He also coaches high school football and relaxes in a wood shop on the family’s property.

Nobody needs to tell Faneca how good he has it. He has a beautiful family and a comfortable living thanks to a lengthy football career. But it’s only human nature to want the one thing missing from a brilliant gridiron resume.

“It’s stressful time,” Faneca said. “It’s stressful on the whole family because my kids are old enough to know what’s going on and they know how the process works and when it’s time to get amped up.”

MAKING A CASE

From the time he began playing high school football in Rosenberg, Texas, Faneca loved the fact he had a hand in the outcome of every game. Competitors thrive on making a difference.

Faneca played the sport while taking medication for epilepsy, suffering his first seizure at age 15. Almost nothing could sideline him. During his 13-year NFL run, he missed one game due to injury.

Many Hall finalists have similar tales. They had to be dragged from the field in order for them not to impact a game.

That’s what makes the Hall-of-Fame process so difficult. Players suddenly are helpless to influence the final tally. It’s up to 48 selectors: sports writers and sportscasters along with Hall-of-Famers like Tony Dungy and Dan Fouts, who are now members of the media.

“The hay is in the barn, man, it’s done with,” Faneca said. “I can’t do anything. I can’t take anything back. My career is done with, it’s played out. You put it in somebody else’s hands, which goes against everything you’ve done as a professional athlete.

“You work, you train hard to make the plays and make the blocks and make the right decisions. I can’t go to the film room to study a little bit more. I can’t go to the weight room to get ready for the next game. The practicing and the playing on Sundays are over.”

Faneca has reached the round of 10 the past few years, putting him tantalizingly close to enshrinement. He figures to have another excellent shot this time.

We’re talking about on offensive lineman elected to the NFL’s All-Decade Team (2000) by many of the same HOF selectors. He was a guard so technically proficient that he committed just four holding penalties in 206 career games for the Steelers, Jets and Cardinals.

Read that last sentence again.

Of course, everyone in line for induction has glowing accomplishments— and the players who run, pass, catch and intercept the ball have stats that are more easily relatable.

“How do you measure a guard like Faneca against a wide receiver,” asked longtime Browns beat writer Tony Grossi, a selector representing ESPN-Cleveland. “That’s one of the hardest things about the evaluation process.”

There’s also the congestion of new players being eligible for induction every year. More names to consider. More competition for the coveted gold jackets. Once a player is out of the league for 25 years -- except for the recent Centennial class -- his only chance at enshrinement is as a senior nominee, and there’s usually only one finalist in that category per year.

Grossi is a Faneca advocate. He saw the left guard play the Browns twice a season and said he’s voted for him in each year of eligibility.

Still, the entire process is bewildering to Faneca and many other outside the room.

“I don’t want to call it politics, but I get the feeling there’s some behind-the-scenes stuff that nobody knows about except the voters,” Faneca said. “It’s all about the logjams. I’ve stopped trying to figure it out.”

He played a position, guard, that is often overlooked. In a game increasingly beholden to passing, offensive tackles are the linemen who get the most recognition.

Faneca has one key stat working in his favor: He is among just 12 guards in league history to earn at least six first-team All-Pro mentions — all the others have been enshrined.

Numbers, however, aren’t what come to mind when Faneca takes measure of his career.

“I came into the league with a bunch of older (offensive linemen) who taught me what this game meant, and I felt empowered as those guys began to leave,” he said. “I felt like it was my duty to carry on what football was about and pass it on to the next generation.”

Life goes on regardless of what the selectors decided Saturday. It’s good to be Alan Faneca either way. But because last year’s enshrinement ceremony was scrubbed due to COVID-19 restrictions, he has the opportunity to enter the Hall in the same ceremony with Cowher, Donnie Shell, Nunn and Faneca’s former teammate Troy Polamalu.

All of that black-and-gold immortality being celebrated on the same August weekend in Canton. Just the thought of it can make a man sleep soundly for one night.